Israel Centeno

I landed in Dover on a spring day like today, more than forty years ago. Back then, I had grand plans. While they weren’t a literal landing, there was indeed a real spring in the kingdom of England. I had told Gladys, with my usual frivolity, “I love that decadent art stuff,” worshipping myself as the only son of God I recognized. I wrote poems about the last two years, left in the streets of Catia, just as I had left my unrequited love for Yelitza on some staircase del cerro, from where I had launched myself in a final test of immortality.

“It doesn’t matter,” I told Gladys, “I have been saved for better arms.” I had crossed France in the midst of a transport strike, spending days sleeping in the Gare de l’Ouest alongside a multitude of stranded travelers, like a refugee camp. During the first days of the strike, I ventured to explore Paris, a city I detest, just like French literature, except for Flaubert. The city assaulted me; it was a foreign body rejected by the manners of those boors who say everything by shouting and insulting. Moreover, it stank.

But now, the kingdom opened up before me, my Dickensian passion, the place I had gone to stretch my nose and learn elegant English. “Gladys,” I told my friend, “I’m going to recite Shakespeare from memory in less than a year.” I had not yet suspected the underworld I would slip into, finding my miserable condition as a squatter, languishing in the coming winter, alongside the impossible love of Vicky, the saddest love story I have had and will ever have. I never told Gladys about Vicky, just as I didn’t tell her about my virginity the day she took it with her rump, on a hot afternoon in Madrid.

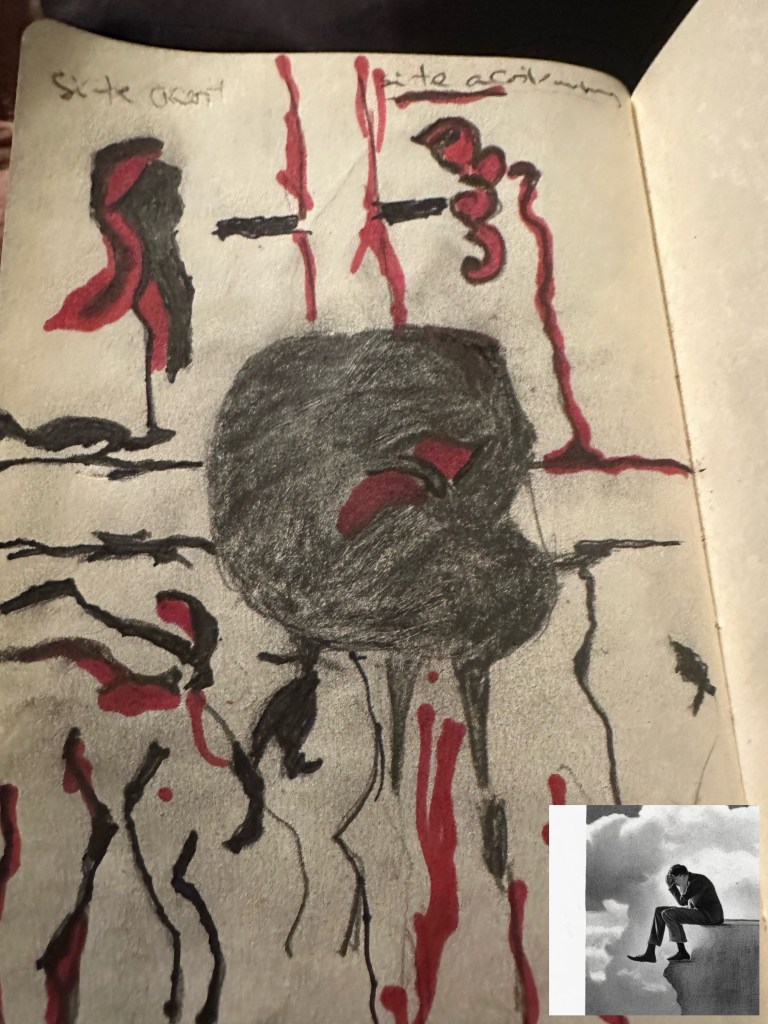

My trip from Dover to London was hallucinated; I hadn’t slept in days, startled by the strikes and the advances of the “faggots” in Paris. I shared the carriage with a prim lady, who seemed Victorian to me, and a girl with a punk crest between green and brown. At some point in the journey, I felt I was leaving my body, my first mystical experience. I left the train and got to see the curvature of the earth from above the British Isles. Below was I, entering my labyrinth, happy and innocent like the perpetrator of a good cause.

Just as I rose, I fell abruptly. I woke up screaming; the lady eyed me sideways, and the punk girl kicked my shin with her boot. The train steward and a burly man subdued me and dragged me to a small cabin. When we arrived at Victoria, dazed, a policeman escorted me to a hospital where I spent a few days in psychiatric care. I made a friend, a paranoid man who, in his narcotic raptures, told me not to worry, that all the crazies became protected by the queen, that the Soviets would never know my whereabouts, and that we would spend our afternoons playing checkers, eating toast with chutney, and drinking tea, as befits every member of the royal household.

The hospital doors opened, and I stepped out into the harsh light of the London day. A black cab waited, its driver with an enigmatic smile. “Where to, sir?” he asked. I looked up at the gray sky, remembering Gladys, Yelitza, Vicky… all the ghosts that had brought me there. “To the palace,” I replied.

Leave a comment