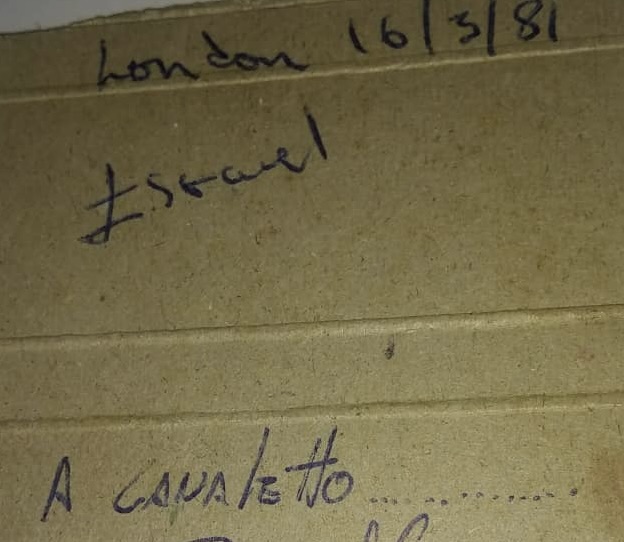

Israel Centeno

When I lived in London, back in 1980, I walked with the innocence of joy through a battlefield. Bombs were exploding, and neighborhoods were burning in Glasgow, Brixton, and Belfast. I enjoyed drinking in Irish pubs; they felt warm, full of life. To me, life was a mix of rage and the desire to tear everything down to start anew. Violence was not foreign to me; I drank deeply from that potion: violence is the midwife of a new society. As a Latin American, I was the heir of bandits and revolutionaries, confused with each other in the trenches of the militias.

I belonged to the generation that, without realizing it, was metamorphosing between the red wings of revolution and the white wings of narcotrafficking. I was red and white, and so I toasted to Belfast with the recklessness of one who believes in heroic deeds. But it was fleeting, for my fall was swift. My disillusionment, like my dreams, was violent. I placed my faith in the transformative power of The Brothers Karamazov and The Devils. I deported myself back to my homeland, and there, with more bitterness than sorrow, I watched the monster of the new movement grow, where the lines between the narco and the revolutionary blurred beyond recognition.

I remember those years in London and feel shame. I could have spent more hours in the Tate Gallery, contemplating Blake’s drawings; more time reading Meister Eckhart, enjoying that spring of ’81, hand in hand with blessed despair on the paths of the bandit. I should have been consistent with my disillusionment and planted myself on Hampstead Hill, to fly a new kite to the sky, always to the sky, like my first prayer on Brixton Hill.

Leave a comment