The end of the fucking world.

Israel Centeno

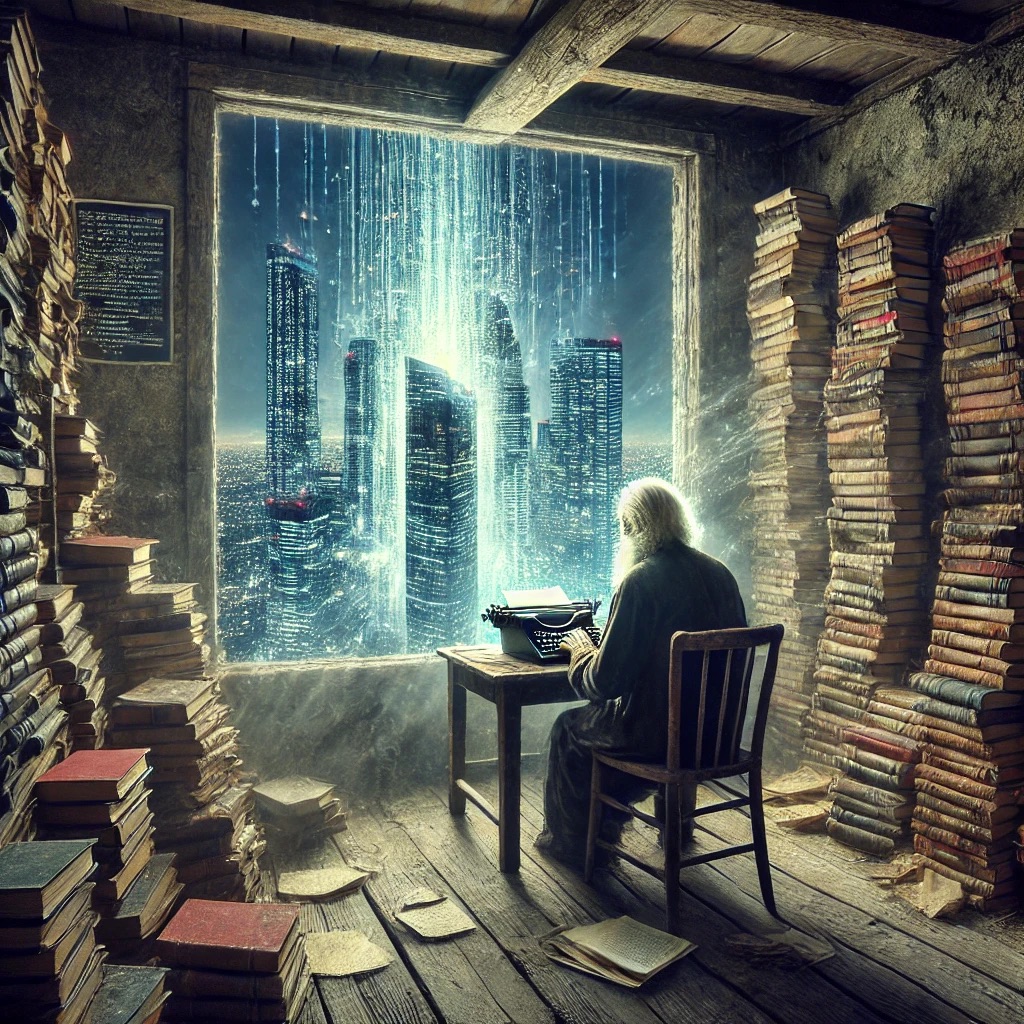

We are at a critical moment in the history of culture, particularly in writing. What was once an intellectual battleground for honest and reflective creation has now been transformed into a space of calculated mediocrity. Content production, whether narrative or articles, has succumbed to a disturbing uniformity, where depth has been sacrificed in favor of immediacy. Readers, trained in this monotony, now seek brief and easily digestible emotional experiences, rejecting any text that requires even minimal effort. I’m not sure if this phenomenon is something I notice simply because I’m an old man with a conservative perspective, or if others feel the same, but the truth is, I only find satisfaction in canonical authors, in the classics. These authors, despite technological advances, continue to represent an artistic quality that seems impossible to replicate in the digital age.

Technology has destroyed entire sectors of culture. Cinema, as we once knew it, has been devoured by computer-generated effects and algorithms that dictate what the public wants to see. Music has been shaped by predictable formulas, where innovation is sacrificed for mass production. The same happens with visual art, now more accessible than ever, but also more emptied of meaning. We only find refuge in museums that exhibit what I call perennial art, the kind that has resisted the erosion of time and trends.

In the realm of literature, writers who still cling to authenticity face a publishing industry no longer willing to take risks on new voices or narratives that challenge the prevailing flatness. Traditional publishing, in many cases, no longer legitimizes. Publishing houses have bowed to a market dictated by algorithms and fast sales, and literary criticism, once serious and methodical, has been consumed by activism and the discourses of university cultural studies departments. What was once a space for reflection has become a showcase for standardized opinions.

In the face of this landscape, writers excluded by this homogeneous machine have only two options: seek out almost non-existent small publishers or self-publish, plunging into the vast ocean of platforms like Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and others. This is not necessarily a negative thing, but in practice, it becomes another reflection of our desperate situation. Authors are forced to navigate a sea of publications that are often no more than manifestations of vanity and narcissism from those who publish to justify their place in life.

Publishing has become absurdly easy. Anyone with a few dollars can do it. But this ease doesn’t imply a greater democratization of quality, quite the opposite: it leads to standardization. Algorithms now decide who will be visible and who will be buried under layers and layers of mediocrity. Technological tools, such as artificial intelligence, only exacerbate this situation. They have turned what was already flat into something even more shallow, presenting the world with a new generation of authors who are nothing more than empty echoes of a mechanized process. These authors don’t need to follow the arduous path of creation; they just need to know how to enter the right prompts into a machine that will do the work for them.

Here, the most disturbing dishonesty of all is revealed. Most of these authors claim to hate the use of artificial intelligence, declare themselves against its intervention in the creative process, yet at the same time, they benefit from it. It’s a dishonesty almost necessary in these dramatic times, where humanity seems to be perishing not from an external catastrophe, but from internal laziness. Forgive the alliteration, but we live in a time where literary production, like many other aspects of culture, is being dragged down by lazy activism of self-promotion. Authors count their “likes” on social networks, seeking superficial approval from people who don’t even read their works.

The important thing is no longer to be read, but that some say they have read you, even if they haven’t. And, worse still, it’s not even important that someone claims to have read you: what truly matters now is that the algorithms say you’ve been read. It’s an absolute perversion of the value of writing, where validation is based on fictitious data, empty likes, and inflated figures by automation. Thus, literary creation has become an increasingly narcissistic and, in many ways, shameless exercise. It has turned into mere self-gratification, where authors see themselves as accomplished geniuses in bubbles within bubbles, immersed in spaces of self-indulgence. But in reality, they are participating in a process of the banalization of art. They publish to fill a superficial void, creating an image of themselves that, in the end, is as hollow as the stories they produce. In this homogenization of literature, artificial intelligence becomes yet another tool to feed that ego, flattening even further what was already shallow.

The problem is not limited to writing. We see it in Netflix, where algorithms also dictate what series should be produced and how they should be structured to maximize screen time. The result is a sense of apathy, of stagnation, where audiovisual narrative lacks risk, novelty, or that impact that used to challenge our perceptions. This phenomenon has become even more dramatic in literature, where writers now produce in series, without the cultural discernment necessary to distinguish between what is good and bad, between what is valuable and disposable. Thus, literary creation has turned into an exercise of mere self-gratification, where authors see themselves as geniuses in their small bubbles, when in reality they are participating in a process of banalizing art.

The world has ended. There’s no need to wait for an apocalypse; we are already living in its cultural manifestation. Writing, the art of telling stories with the intelligence and insight of our ancestors, has been suffocated by intellectual laziness and algorithms. We no longer need to wander from agent to agent, from publisher to publisher, seeking approval. Now, we only need money and a good algorithm to be buried in the vastness of homogeneous publications flooding the market.

The most disturbing aspect of all is that this phenomenon has also reached the generators of philosophical thought. From Google search engines to artificial intelligence services, we’ve reached a point where the minds that should be leading critical thought have also been absorbed by this machinery of mediocrity. We’ve lost control, surrendering ourselves to the end of the cultural world, where writing and artistic creation have been replaced by a void of prompts and automatic responses. And meanwhile, we, the writers, who once believed in the transformative power of words, find ourselves alone, watching how everything we loved has been stripped of its value.

This is the end of the world.

Leave a comment