Israel Centeno

In the past 24 years, Venezuela has experienced a continuous and sustained cultural, historical, and religious fracture, leading the country to suffer from a profound dysphoria. As a collective, we feel deep shame, discontent, and unfamiliarity. We believe we do not recognize ourselves, as any reference that defined us as a nation has been erased. One of the most significant of these is having been a nation forged by one of the most admirable historical figures of all time.

Two geniuses were born in the city of Caracas and were contemporaries: one was Simón Bolívar, and the other, Andrés Bello. One emancipated us from the despotism of the Spanish crown, and the other bequeathed us a grammar that would allow us to exercise that emancipation with the knowledge of one who masters their language well. As heirs of these architects of republican Venezuela, we have lost our way because they have been manipulated time and again to endorse political projects that were almost always alien to the ideals of those they claimed to emulate.

In rejection of the so-called “Bolivarian revolution” imposed by Chávez, many Venezuelans, instead of delving deeper into the works and letters of the Liberator, began to engage in a harmful revisionism that would culminate in the spirit of the 1830s, repudiating Bolívar at the mere mention of his name.

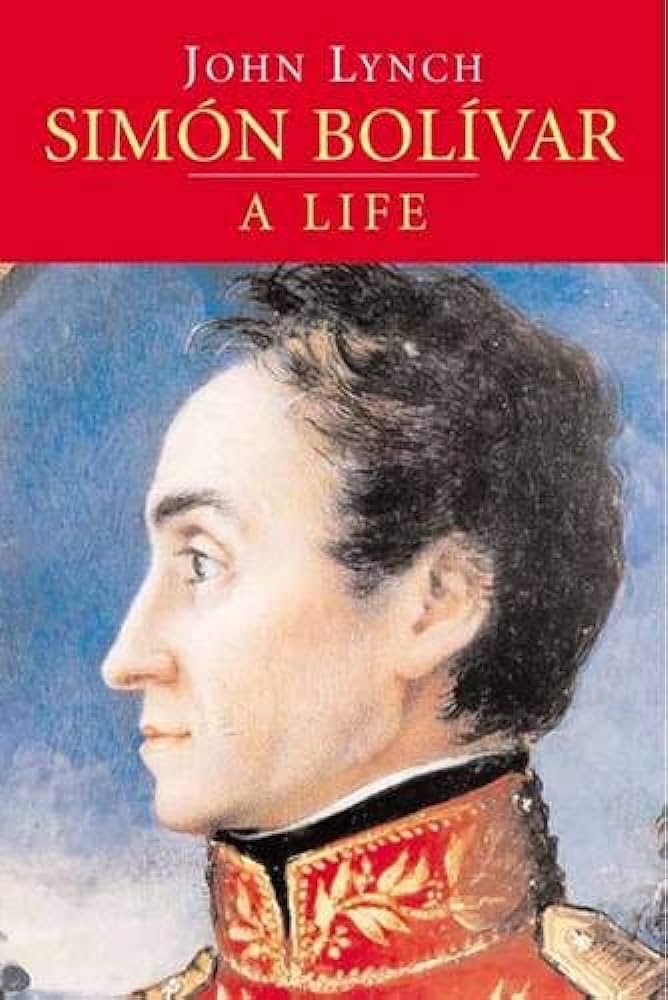

Today, I have approached the Liberator anew—a title he will never lose. A title I read in its particular context. I have been aided by reading a biography by the English writer John Lynch. It is an engaging book that does not distort merits and does not diminish the exceptional man born in Caracas in 1783. Its historical sources are precise, free from any demagogic brushstrokes; its prose is not overloaded with empty nationalist or patriotic adjectives. There is an attempt, in my understanding very well achieved, by this gentleman who authored this relatively new biography of Simón Bolívar, to present him to us as he truly was: the man of difficulties, the man who overcame any adversity to carry forward a project that, lacking peers who could understand it, collapsed before his eyes just before he died in Santa Marta in 1830.

Bolívar, a man who rode 77,000 miles, who conducted a campaign from the Orinoco to Upper Peru, not only liberating nations but also decreeing the emancipation of their slaves and the equality of their inhabitants. I am now left with the curiosity to read the memoirs of O’Leary; they are several volumes, and I imagine they must be truly delightful.

Leave a comment