Israel Centeno

My early readings were not a foundation guiding me toward building a better world or leading a fuller life. On the contrary, they dissected my thoughts and poured venom and smoke into them. In my youth, I was thrilled to read that the revolutionary must understand revolution as the ultimate act of love, expressed by becoming a cold killing machine. That was how Che’s first diary in the Sierra Maestra captivated me: a manifesto that justified violence as a method of redemption.

Later, Nietzsche, with his intellectual games, replaced the worship of God with the worship of an indestructible man, almost a god. According to him, a God who became man was weak and responsible for the fall of the Roman Empire. Instead, man must become God, surpass himself, and break any social order that weakened him. To this was added the propaganda of Lenin and Mao, which shaped an ideological powder keg in my mind with no counterbalance other than the laments of Hesse.

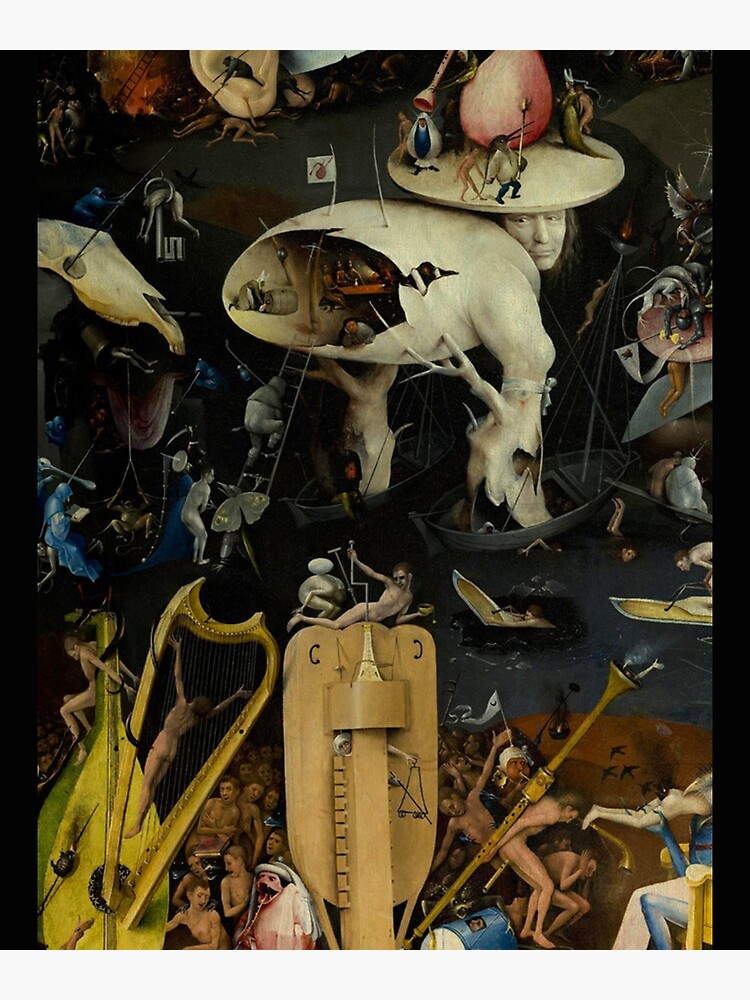

My mind was a battlefield, and my body sought adrenaline in destructive action, for destruction was a creative, Dionysian act. Imposing readings like The Myth of Sisyphus and The Stranger by Camus, reinforced by the adventures of Young Werther and Hamlet by Shakespeare, on a young person was a crime. These works, with their melancholy and questioning of life’s meaning, fueled my craving for chaos and rupture.

The world of reading is dangerous. However, like the prince who crosses a thorny forest that blinds those who lose their way, I managed to come out with my eyes intact. But not without scars.

To this was added the vileness of the cult of Sade, sexual liberation, and the disorder of the senses promoted by romantic poets. It is easy to get lost, especially when you lack a structure designed to metabolize an order you’ve learned to despise. If the entire bourgeois world seems like a place that must be blown to pieces, you end up rotting from within. You resemble the hidden portrait of Dorian Gray and celebrate it as Maupassant celebrated his syphilis.

You must dare to say: fine, Rimbaud was a genius, but he was also a sorcerer, a malignant figure in Verlaine’s life, a bastard who ended up trafficking weapons in Africa.

You’ll be lucky if you don’t end up in an asylum howling like a dog. In my case, the panic attack was my shadow line. I stopped rowing and allowed other authors to enter my life because my soul, at the extreme point of dryness, was beginning to crack and wrinkle.

That was when I discovered Dostoevsky. In Demons and Crime and Punishment, I found an unrelenting depiction of nihilism but also the possibility of redemption. Dostoevsky showed me that evil is not an abstraction but a force that tears at the soul and, despite this, opens a path to reconciliation with the divine. Gradually, transitioning from Camus’s existentialism to Eckhart’s mysticism became a necessity, though not without resistance.

From French literature, I rescue Chateaubriand, Stendhal, and Flaubert. The Red and the Black gave me an aesthetic ecstasy that built a bridge from that garden planted with warts to a more serene center of life. In Stendhal, man no longer seeks destruction but survival with dignity within an order to which he does not belong. It’s a necessary counterpoint to escape chaos.

I left behind the Dionysian mirages and began to embrace balance. Borges was pivotal in this process. In his work, I found an infinite library that reconciled reason and wonder, order and mystery. Homer, that blind man who sees beyond the visible, became the poet I wished to be. In Chesterton, I found a warm embrace and the gaze of one who knows how to give evil its weight without granting it the final triumph.

Finally, the Bible. A good translation of the Jerusalem Bible became my rock. With its stories, its proverbs, and The Song of Songs, I discovered a literary and spiritual universe beyond compare. Even when God shows himself as terrible against those who sacrifice their children to Moloch, the burning bush in the desert lights the way. That image of Yahweh’s back on Mount Sinai, the strength of the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah, and the Psalms that console and torment became part of my redemptive horizon.

Now, I look back and see that my early readings were a necessary danger. Reading is not a pleasure; it can be an intense source of suffering and constant confrontation. Those readings led me to the abyss but also showed me the way out. Literature is both a thorny forest and a lighthouse, a poison and an antidote. And though the journey was perilous, I came out whole, with open eyes and a rebuilt soul.

Leave a comment