Israel Centeno

The relationship between sensuality, spirituality, and transcendence has been explored in different ways across religious traditions. In Tibetan Buddhism, particularly in Tantra and Vajrayāna practice, sensuality is often integrated into the path of enlightenment. This contrasts sharply with the Christian understanding of love and the human body, particularly as articulated in the Theology of the Body by Saint John Paul II. While both traditions recognize the power of desire and the body, they interpret its purpose and ultimate meaning in profoundly different ways.

The Role of the Body in Spiritual Practice

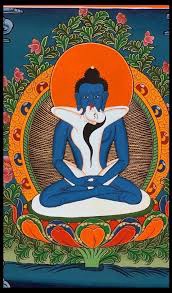

Tibetan Buddhism, especially in its Tantric or Vajrayāna forms, views the body and sensual experience as tools for achieving enlightenment. Unlike more ascetic Buddhist traditions that emphasize detachment from physical pleasure, Tantra embraces the idea that bodily experience—when properly directed—can become a vehicle for spiritual realization. The body is not merely a hindrance to enlightenment but a dynamic means of awakening to the ultimate nature of reality.

In contrast, Christian thought—particularly in the Theology of the Body—sees the human body as a sacred expression of personhood, created by God as part of His divine plan. While physical desires are not inherently sinful, they must be ordered toward love and self-gift rather than personal gratification. The body is not merely a tool for transcendence but a sign of the spiritual dignity of the person.

Sensuality and Desire: Means or End?

A fundamental divergence between Buddhist Tantra and Christian theology lies in their understanding of desire. In Vajrayāna practice, desire is neither wholly rejected nor uncritically indulged; instead, it is transformed. Tantra teaches that by engaging with sensory experience—including sexuality—one can transmute desire into a higher state of awareness, ultimately realizing the illusory nature of the self and the world. This process involves elaborate rituals, meditative visualization, and even sacred union (maithuna) in some esoteric contexts. The goal is to harness sensual energy and redirect it toward enlightenment.

In Christianity, desire is understood differently. The Theology of the Body affirms that human love and sexuality are ordered toward a personal communion that mirrors the divine love of the Trinity. Sensuality is not a means of transcending the self but of fully realizing one’s self in relation to another. Love, as defined in Christian theology, is not merely an energy to be transmuted but a personal act of self-gift. The ultimate fulfillment of desire is not found in mystical absorption but in a relationship—whether in marriage, celibacy, or the divine union of the soul with God.

The Purpose of Union

Both traditions recognize union as a central spiritual goal, but their definitions differ significantly. In Buddhist Tantra, union—whether symbolic or literal—is often framed in terms of the integration of opposites: male and female, wisdom and compassion, emptiness and form. The practitioner seeks a dissolution of duality, ultimately realizing that all distinctions, including the distinction between self and other, are illusory.

In Christian theology, union is not the erasure of difference but the fulfillment of it. The relationship between man and woman, for example, is not about dissolving individual identity into an abstract oneness but about forming a communion of persons. This is why marriage is seen as an image of Christ’s love for the Church—it is a total self-gift in which distinction is preserved but transformed by love. Even in celibacy, union with God is not about losing personal identity but about finding it fully in the divine presence.

Liberation vs. Redemption

Both Buddhism and Christianity address the fundamental problem of human suffering, but their solutions are different. Tibetan Tantra, like other Buddhist traditions, ultimately aims at liberation from the cycle of rebirth (samsara) through enlightenment. The world and the self are seen as transient, and spiritual practice is directed toward realizing their illusory nature. Sensual experience, in this framework, is not an end in itself but a method for accelerating the path to non-attachment.

Christianity, however, does not seek liberation from existence but its redemption. The world is not an illusion to be transcended but a creation to be restored. The Christian hope is not to dissolve into an abstract oneness but to participate in the divine life through grace. Salvation is not the realization that there is no self but the fulfillment of the self in God’s love.

Conclusion: Two Paths, Two Ends

Tantric Buddhism and the Theology of the Body both take sensuality seriously as a component of human experience. However, their ultimate aims are irreconcilable. Tantra sees the body and desire as instruments for enlightenment, tools that, when properly mastered, help the practitioner transcend duality and selfhood. Christianity, on the other hand, sees the body as an intrinsic part of the human person, and desire as a call to self-gift rather than transcendence.

One tradition seeks liberation through dissolution; the other seeks fulfillment through communion. One treats the body as a vehicle for transcendence; the other as a sign of divine love. Both paths recognize the depth of human longing, but they lead in opposite directions—one toward the extinction of the self, the other toward the embrace of a love that endures beyond time.

Leave a comment