Whoever takes up the sword shall perish by the sword. But whoever does not take up the sword—whoever relinquishes it—shall die on the cross.

In Christ’s miracles—the healing of the sick, the raising of the dead—lies the humble, almost lowly, aspect of his mission. These acts, though divine, touch only the surface of his purpose. The true supernatural mystery is found in his agony, in his sweat of blood, in his desperate plea for comfort, in his final cry of abandonment: “My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?”

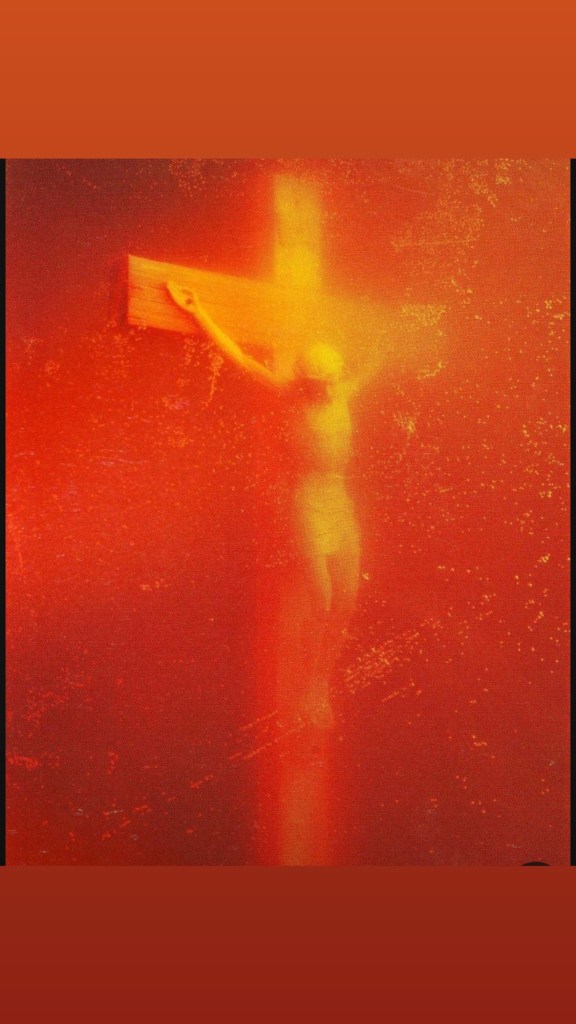

This moment, in all its darkness, is the mark of Christianity’s divinity. It is not in power, but in utter desolation, that the deepest mystery unfolds. The cross stands beyond imagination, beyond imitation. No one seeks it. No one desires it. Heroism can be willed, asceticism chosen—but the cross is an affliction laid upon the innocent.

To remove the suffering of the cross, to see it only as an offering, is to strip it of its bitterness and its power to save. The cross is infinitely more than martyrdom. It is the final guarantee of authenticity: to be forsaken by man, to be forsaken even by God, and still to endure.

Simone Weil

My Version of Gravity and Grace by Simone Weil, Rethought in Greek Chants

Israel Centeno

To monseñor Roberto Sipols apóstol de la cruz

Whoever takes up the sword shall perish by the sword.

Whoever lays it down shall die upon the cross.

In the hands of men, power takes the form of violence.

In the hands of God, power takes the form of surrender.

Between these two, the world stands suspended,

not knowing how to choose,

not daring to let go.

To grasp the sword is to invite death.

To let go of the sword is to walk toward something greater,

though that path leads first through suffering.

I. The Tree of Knowledge and the Tree of Sacrifice

Once, in a garden, there stood a tree.

It bore fruit, golden and full,

and men reached for it, believing it held divinity.

That tree gave knowledge,

but knowledge without wisdom

becomes a burden too great to bear.

So another tree was raised,

this one cut from living wood,

its branches stripped,

its arms measured and squared.

It bore no fruit,

no shade,

only a body nailed upon it.

One tree, the hunger for divinity.

The other, the answer to that hunger.

One, the desire to be like God.

The other, the surrender to being man.

II. The Cry of Abandonment

Christ, who healed the sick,

who raised the dead,

who fed the multitudes—

this was the Christ of power,

the Christ men could understand.

But the Christ of the cross?

The Christ who sweat blood in the garden?

The Christ who stretched his arms in agony,

who cried out into the silence,

“My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?”

This Christ is a scandal.

This Christ is an abyss of love

too terrible for the world to look upon.

Here, in the darkness of divine abandonment,

God experiences what it means to be fully man.

To suffer.

To thirst.

To feel the weight of silence pressing down.

The greatest act of divinity

was not in miracles,

but in this:

God made powerless,

God made flesh,

God emptied,

God forsaken.

And yet—

this is the moment of salvation.

III. The Journey of the Soul and the Journey of God

From the depths of time and space,

God stretches toward the soul,

seeking to claim it.

For an instant—

one pure moment of consent—

the soul surrenders.

Then, silence.

God, having taken the soul as His own,

abandons it.

Now the soul must cross the abyss in return.

Not as it was found,

but as one stripped of certainty,

stripped of self,

walking blind into the unknown.

This is the cross.

This is the return.

IV. The Crucified God

God is nailed down

not by iron,

but by the thoughts of men.

To be human is to be God crucified.

To be divine is to wear the chains of necessity.

To love beyond all limits

is to suffer beyond all limits.

Prometheus, bound for giving fire.

Hipólito, torn for his purity.

One punished for loving men too much,

the other for loving the gods too well.

Between the divine and the human,

love is always suffering.

V. The Distance Between God and Man

We are the ones furthest from God.

We live at the edge—

where return is still possible,

but nearly impossible.

The love of God is suffering,

because love stretched over an infinite distance

tears apart all that stands in between.

To sense the gulf between man and God,

it is not enough to imagine a Creator.

One must look upon the Crucified.

It is easier to dream of God as ruler of the heavens

than to imagine oneself in the place of the abandoned Son.

The greater the love,

the greater the distance,

the deeper the wound.

VI. The Innocent and the Weight of the World

An innocent who suffers

becomes light for the condemned.

A child’s blood on the snow,

a pure wound in the body of the world—

such suffering is the only pure form of evil.

And yet, when the innocent suffers,

the weight of the universe shifts.

The scales are tipped.

A counterweight is thrown.

To be innocent is to bear the whole weight of the world.

It is to be crushed by it,

and in that crushing,

to empty oneself completely.

To empty oneself

is to become open to all suffering.

To open oneself

is to let the pressure of the universe descend.

VII. The Final Surrender

The final act is not to conquer,

but to surrender.

The final step is not to rise,

but to be lifted.

To empty oneself completely,

to give without return,

to suffer without explanation,

to love without demand.

And in that surrender—

in that death—

is resurrection.

Leave a comment