Israel Centeno

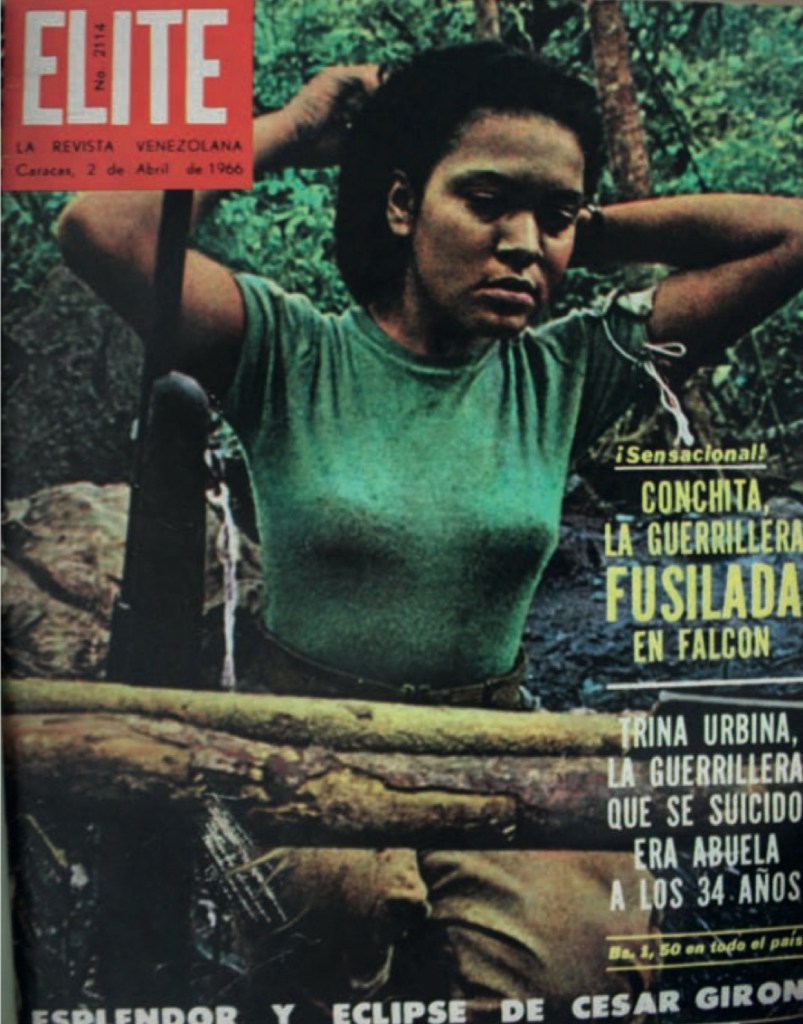

In April 1964, in the mountains of Falcón, several guerrillas from the José Leonardo Chirinos Front were executed by order of acting commander Félix Farías. Among those executed was Conchita Jiménez, accused of attempting to desert, demoralize the group, and, according to witnesses, of reporting an attempted sexual assault by the top insurgent leader, Douglas Bravo. A few days later, Trina Urbina, a worker and communist militant known as “Trina the guerrilla,” committed suicide by shooting herself in the chest. She had supported the executions.

These events occurred far from Caracas, but their echo has been manipulated for decades. At the time, they were justified as measures of revolutionary discipline. Years later, they were silenced or turned into anecdotes by official historiography. Today, these deaths weigh more heavily than the commemorative speeches.

Félix Farías, the same man who ordered the executions, would die three years later in a confrontation with the police in the José Félix Ribas neighborhood of Petare. For the Bolivarian government, his figure has been turned into that of a martyr. His name appears on lists of heroic fighters, without much review of his actions. But those who have studied the archives and testimonies of the time, such as Agustín Blanco Muñoz and Gioconda Espina, tell a different story: that of erratic, authoritarian leadership, deeply marked by jealousy, personal passions, and internal repression.

Conchita Jiménez was executed for speaking out. Trina likely shot herself because she couldn’t live with the burden of having remained silent. Both were women in an armed structure that never fully recognized them as combatants. Argelia Laya warned years later: many women were not allowed to join the guerrilla because “they were not to be used.” But those who did join, who fought, ended up marginalized, executed, or silenced.

There is something deeply disturbing about the way the Venezuelan insurgent movement of the 1960s resolved its internal conflicts. What should have been a political struggle ended up being a chain of summary sanctions, moral lynchings, and executions without fair trial. Those who opposed state repression reproduced similar structures in their own camps.

Douglas Bravo, attributed with strategic and political leadership in the Venezuelan insurgency, has been identified in multiple testimonies as a figure who, at the very least, allowed or covered up these abuses. In the accounts collected by Lino Martínez and other researchers, it is clear that the commanders did not know or did not want to stop the internal tensions and rivalries that led to unjustified deaths.

There has been a systematic romanticization of the guerrilla. The image of the noble fighter, of Korda’s Che, of sacrifice for the people, has been repeated ad nauseam. But in the mountains of Falcón, the struggle was neither clean nor heroic. It was confusing, chaotic, and often cowardly. The testimonies of the time—by combatants, relatives, historians—speak of jealousy, exemplary punishments, executions ordered out of fear, not justice.

The case of Trina and Conchita exposes this anti-epic. There is no redemption in that end. There is no revolutionary glory. There is death. There are mistakes. There are complicit silences. And there is an uncomfortable legacy that today is being glossed over with commemorative plaques and official honors.

Félix Farías, the same man who participated in the kidnapping and torture of Iribarren Borges, is mourned as a victim. But he died in combat, armed, facing the police, as part of a struggle he chose and led with brutality. He died as he lived: with a rifle in hand and without being held accountable for his decisions. He was not unjustly killed. He was a man who made punishment and violence his form of leadership and ended up being brought down by that same logic.

Recent history celebrates him. But critical memory cannot afford that luxury. Because as long as statues are erected to the executioners, the true victims will remain buried in the ravine of silence.

Leave a comment