Israel Centeno

This is not about defending Trump—whom I view with skepticism and, at times, harsh criticism—because I do not believe in idols or political or military redeemers. I do not believe in human saviors. A single man and his will can only bring great disasters. The greatest achievement of civilization lies in institutions that keep each other in check—some of us call them republics, others parliamentary monarchies, and so on. The figure of the strongman leader is one I came to loathe in Venezuela, and I still loathe it now. I am deeply disturbed by the current U.S. president’s taste for bypassing institutions and ruling with the demeanor of an emperor awakened from some expansionist dream. His rhetoric, reminiscent of the first Roosevelt, is not harmless: he has spoken of annexing Canada or Greenland, even of renaming gulfs and mountains. These are not trifles. Politically, I am clear-eyed and disappointed. There are no pure sides. The truth is that the future seems to be shaping into an era of functional illiberalism—comfortable authoritarianism for some, new orders where comfort is valued more than liberty. There is an authoritarian, anti-liberal revolution underway, and like Marx’s old specter, it now haunts the world. Those who once shouted “reset” are enacting the true reset, and we are all walking, more or less, along the edge of a dulled razor. If that is the price, then it’s time to begin writing again—clearly.

That said:

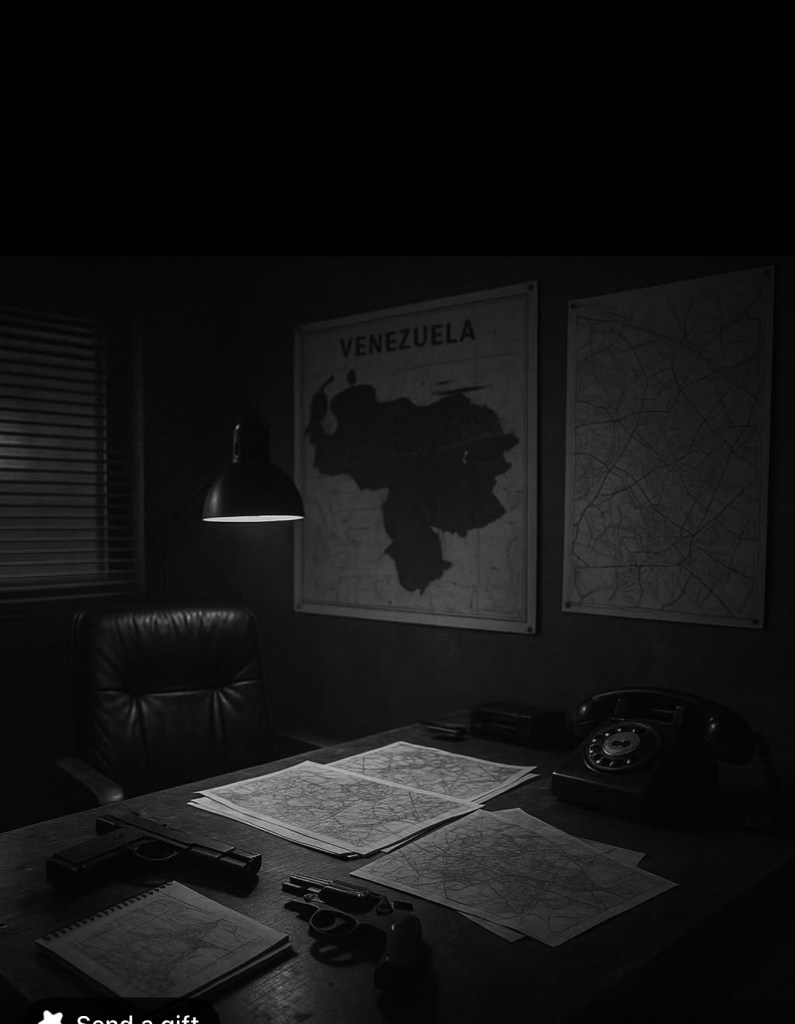

This is not Trump’s fault. Nor the embargo’s. Nor some global conspiracy. The tragedy that has bled Venezuela dry and now spills across Latin American borders has clear names and surnames: Nicolás Maduro Moros and the chavista machinery that, in two decades, turned a democratic republic into a narco-state. The diaspora of more than seven million Venezuelans was not a geopolitical accident but the direct result of a systematic policy of dispossession, persecution, militarization, and corruption. What follows is the chronicle of an inevitable consequence: the emergence of a criminal organization—the Tren de Aragua—nurtured, protected, and, as is now judicially suspected, used as an instrument by the Venezuelan state itself.

Chavismo did not merely dismantle institutions; it hollowed them out to turn them into the façade of a total-control project. The military became a smuggling enterprise. The prisons, criminal fortresses. The Ministry of Penitentiary Services, a mafia incubator. The judiciary, a mute accomplice. From within this structure, groups like the Tren de Aragua were born and spread—first through the barrios of Maracay and Caracas, then across national borders, infiltrating migrant routes, extorting in Lima, killing in Santiago, and organizing in New York.

When Ronald Ojeda was kidnapped and murdered in Chile, the country’s justice system had no doubts about where the thread led: Caracas. A protected witness, member of the “Los Piratas” cell of the Tren de Aragua, testified that Diosdado Cabello ordered and financed the killing. The statement was not isolated—it came with data, locations, timelines, and payment records made in Peru. Chavismo’s reaction was predictable: deny everything, insult Chilean prosecutors, deflect the spotlight. But this time, the accusation was too precise, too serious, and too credible to be dissolved in a sea of propaganda.

On the fringes of Venezuelan legality, under the protection of a penitentiary system turned haven for criminals, a structure was born that now symbolizes the moral, institutional, and geopolitical collapse of the region: the Tren de Aragua. This criminal network not only dominates territories within Venezuela but has exported its model of terror, extortion, and murder to countries like Peru, Colombia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, and more recently, the United States. What’s most disturbing, however, is not its reach, but its increasingly clear ties to the Venezuelan state. What was once hinted at is now being documented: the Tren de Aragua has not only grown in the chavista shadow, it may have carried out crimes on behalf of the regime.

The murder of former Venezuelan lieutenant Ronald Ojeda in Santiago, Chile—kidnapped by men dressed as Chilean police in February 2024 and later found dead inside a cement-sealed suitcase—brutally exposed this convergence of crime and politics. The judicial investigation was unequivocal: a protected witness from the Tren de Aragua’s “Los Piratas” cell stated that Diosdado Cabello, a powerful figure in chavismo and president of the National Assembly, had ordered and financed the crime. According to the testimony, the payment was made in Peru to the cell’s leaders, though lower-level operatives received nothing. Chile’s prosecution supported the weight of this testimony, classified the crime as political, planned from Caracas, and initiated proceedings to bring the case to the International Criminal Court.

These grave accusations have strained Chile-Venezuela diplomatic relations. Cabello’s indignant denial—“Fix your problem over there in Chile,” he said on live TV—only confirmed, in the court of public opinion, the arrogance with which chavismo responds to such serious charges. For Ojeda’s family and for the governments receiving waves of Venezuelan migrants, the suspicion is no longer mere speculation: the organized crime expanding in their streets bears the Venezuelan state’s stamp, and its impunity is guaranteed by those still seated in Miraflores Palace.

The Tren de Aragua was incubated in the Tocorón Penitentiary Center, its headquarters, where a prison control system managed by internal gang lords—known as pranes—was tolerated and often supported by the Ministry of Penitentiary Services under Iris Varela’s long tenure. From there, the gang’s tentacles extended: first into vulnerable Caracas neighborhoods, replacing the state in managing violence; then into mining zones in the south; and finally, riding the waves of migration, into much of Latin America. Along this criminal trail, it has engaged in extortion, human trafficking, contract killings, kidnapping, and drug trafficking. Its operational logic is closer to that of a transnational franchise than a local gang.

There are disturbing parallels with Cuba’s recent history. In 1980, Fidel Castro used the Mariel boatlift not only to expel dissidents but also to send criminals, sowing chaos within the enemy’s borders. Chavismo, though not overtly pursuing a similar policy, has produced a comparable effect. Amid Venezuela’s collapse, millions have fled—and among them, silently and armed, have traveled Tren de Aragua operatives. Their presence in Lima, Bogotá, Santiago, or Cúcuta is neither random nor improvised: they exploit migrant vulnerability and institutional weakness to sow fear and take control of informal economies and marginalized zones.

Today, the Tren de Aragua is extorting shopkeepers in El Callao, embedding in migrant communities in New York, Chicago, and Miami. It works alongside local mafias and is linked to crimes ranging from human trafficking to murder-for-hire. U.S. authorities have acknowledged it as a real threat. This is not merely a Venezuelan issue: it’s a hemispheric criminal phenomenon.

But it is in Venezuela where it was conceived, nurtured, and protected. The line between state and organized crime has eroded. It is no exaggeration to say that the Tren de Aragua is the paramafioso phase of chavismo. This is not just about impunity—it is about active complicity, as the Ojeda case illustrates. For a criminal gang to assassinate a dissident in a foreign country at the behest of a high-ranking official reveals a systematic state practice, typical of authoritarian regimes that export their persecution beyond their borders.

The Tren de Aragua cannot be dismantled by patrols, media campaigns, or indiscriminate crackdowns alone. It must be confronted through international justice, intelligence cooperation, and above all, with the political will to name things for what they are: a transnational criminal organization shielded by an authoritarian regime. If not stopped, its power will consolidate into a parallel state, not only embedded in Venezuelan prisons, but entrenched in the peripheries of Latin America and the shadows of the hemisphere.

Leave a comment