An Easter Meditation in the Age of Images

Israel Centeno

We live in the age of cameras. In the age of the cell phone always in hand. Everything is recorded, everything is photographed, everything is uploaded. Every moment is captured in an image, every face wants to be seen, every body searches for the right angle, a filter, an approval. But there is one image that was not taken by any camera, that was not staged, that was not made for a social network nor to impress. An image that does not change with time, that needs no editing, no effects, no retouching. An image that, quite simply, cannot be explained.

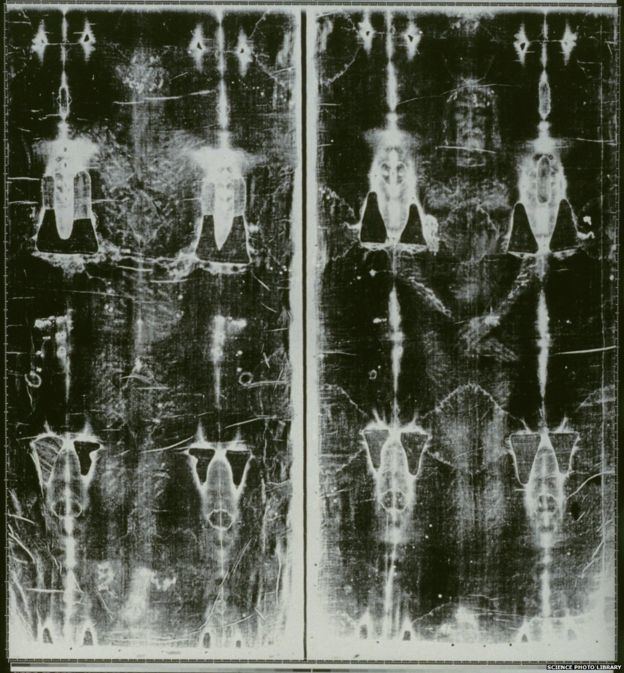

It is the image that remained on the Shroud of Turin. A face. A whole body. From the front and the back. Covered in wounds, but standing. As if at the exact moment He came back to life, the Lord had left us a selfie. The only one. The definitive one. The one of His victory.

It was not made with ink, nor with pigment, nor with pressure. The most rigorous scientific tests—X-rays, infrared analysis, spectroscopy, electron microscopy, three-dimensional and fluorescence studies—have found no trace, no paint layer, no known composition. And yet, there it is: a perfect negative. An image that only fully reveals itself when light is inverted, like in old photography. But this image was not taken with visible light; it was literally imprinted by a radiation so intense that it neither destroys nor consumes: it simply reveals.

And then we understand that this light is not just any light. It is the light Moses saw on Sinai, the one that wrote with fire on stone. The light that made his face radiant when he came down the mountain. It is the same light that surrounded the burning bush that was not consumed. It is the light of Tabor, the one that blinded Peter, James, and John when Jesus was transfigured before them and His face shone like the sun. It is the light of the Resurrection. A light that not only illuminates: it transforms. That does not burn the cloth, but leaves on it the image of the living God. A light that, instead of killing, gives life. And life in abundance.

Today, neither the best designers, nor the brightest scientists, nor the most advanced artificial intelligence has been able to replicate it. And yet, there it is. On a piece of ancient linen, fragile, silent. As if saying: “I am alive. And I have left it in writing. Not in ink, but in light.”

And if it were a medieval invention—as some have suggested—we must ask: who in the 13th century knew how to project a negative? How to print volume on a flat surface? How to encode three-dimensionality? How to represent an image without pigments? How to align with absolute precision each of the wounds of the Passion as narrated in the Gospels?

Because that is the most overwhelming part: all the marks are there. Every one. With surgical precision. The lacerations from the Roman scourge, from shoulders to ankles. The signs of the crown of thorns, not just on the forehead as in paintings, but around the whole head, as if it had been entirely covered. The wound in the side, on the right, oval in shape, consistent with a Roman spear. Scraped knees, a broken nose, facial bruises, the rigidity of the corpse, bloodstains of human type AB. Everything is there. Everything matches.

And one detail that overturns centuries of iconography: the nails do not go through the palms, but through the wrists. Precisely where the body’s weight would not tear the flesh, as Roman practice dictated. Something no medieval artist would have guessed.

And the hair… the hair does not hang like that of a corpse lying horizontally. It falls like that of a man who is standing. Standing. Not collapsed. Not defeated. Standing as one who rises. As one who passes through the shroud from the inside out. As one who—in absolute silence—conquers death.

This image is not that of a decomposing body. There are no signs of decay. No shifting. Everything indicates the body was wrapped for only a short time. And then, in an ungraspable, unpredictable, irrepressible moment… it disappeared. As if it had passed through the cloth without tearing it. As if the cloth had remained embracing the glorious emptiness of a risen body.

And then one understands that this image, this selfie of God, is not a trick, not a superstitious relic, not a museum piece. It is a sign. A signal. A silent word that speaks to this hyper-visual age with an impossible image. As if saying: “You didn’t need to see me to believe. But now that you believe in nothing… look.”

And when one contemplates it, everything becomes clear. It must not be idolized. But it also cannot be ignored. Because in that body are our wounds, our betrayals, our death. And yet, that body is alive. And no filter or effect can enhance it, because it is the ultimate beauty: the beauty of Love that does not give up.

Jesus didn’t need to leave proof. The empty tomb would have sufficed. But perhaps, knowing how faith would fade in the final times, He left us an image. Not to prove. To provoke. To provoke wonder. So that we would know that yes, He rose. And He did it carrying the full weight of our misery. And that His resurrection was not just for Him, but for us.

In that shroud remained the body of a man who died, yes. But more than that: the body of God who reclaimed life. The body of the Son who, standing up, opened an eternal portal. And said, with light engraved on linen: “Death, where is your sting?”

Today, in this century of screens, God’s selfie is still there. We cannot replicate it. We cannot explain it. We can only look. And in looking, let hope reignite within us.

Because death has no power over Him.

Nor will it have over us.

Because we live in Him, through Him, and for Him.

And that—that—is **Easter

Leave a comment