Israel Centeno

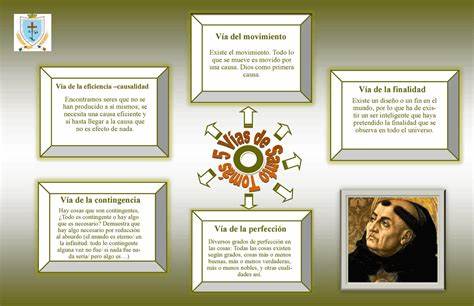

Santo Tomás propone cinco caminos para demostrar que Dios existe, partiendo no de la fe, sino de la razón. Estas cinco vías están en su Suma Teológica y parten de lo que todos podemos observar en el mundo. No son pruebas matemáticas, sino argumentos filosóficos inductivos, desde la experiencia hacia el Principio último.

1. Vía del movimiento (o del cambio)

Todo lo que se mueve es movido por algo.

Ejemplo: una piedra se mueve porque alguien la lanza.

Pero no podemos tener una cadena infinita de “movedores”.

Tiene que haber un primer motor inmóvil: eso es Dios.

2. Vía de la causa eficiente

Nada se causa a sí mismo.

Ejemplo: una flor nace de una semilla, que viene de otra flor, etc.

Pero no puede haber una cadena infinita de causas.

Debe existir una Causa Primera que no haya sido causada: eso es Dios.

3. Vía de lo contingente y lo necesario

Todo lo que existe pudo no haber existido. Es contingente.

Pero si todo fuera contingente, en algún momento no habría existido nada.

Debe haber un ser necesario que dé existencia a todo lo demás: eso es Dios.

4. Vía de los grados de perfección

Vemos cosas buenas, mejores, más bellas, más justas…

Y medimos esos grados comparándolos con un máximo.

Debe existir un ser que es la máxima Bondad, Belleza, Verdad: eso es Dios.

5. Vía del orden o del fin (teleológica)

Las cosas sin inteligencia (como el sol, el ADN, el instinto) actúan con orden.

Ese orden no puede venir del azar.

Debe haber una inteligencia suprema que dirige todo hacia un fin: eso es Dios.

¿Qué hace Edith Stein con estas cinco vías?

Edith Stein, discípula de Husserl, conversa con Santo Tomás en clave fenomenológica, existencial y mística. En su obra Ser finito y Ser eterno, no se limita a repetir las vías, sino que las interioriza, las eleva y las cruza con su búsqueda del Ser absoluto.

- Toma en serio el límite del pensamiento moderno: ya no basta con demostrar a Dios como “motor inmóvil”. El ser humano busca algo más que una Causa: busca sentido, plenitud, ser, en el sentido profundo.

- Profundiza la tercera vía (contingente-necesario):

Para Stein, el ser contingente —el nuestro— no se sostiene por sí mismo. Necesitamos participar de un Ser que sea plenitud de ser, lo que ella llama el Ser eterno. Y ese Ser no es solo acto puro: es Amor personal, plenitud comunicativa. - Desde la quinta vía (orden y fin), ella descubre intencionalidad:

El mundo tiene sentido porque está ordenado hacia algo, y la conciencia humana misma busca dirección. Ella conecta esto con el dinamismo de la gracia y la vocación del alma. No solo hay un orden cósmico: hay una orientación existencial hacia el Absoluto. - Contrasta esto con la visión poética de Hölderlin, que canta la nostalgia del Absoluto, pero sin poder afirmarlo. En Hölderlin, Dios es ausencia, ruptura, belleza inalcanzable. Para Stein, en cambio, el Ser eterno se revela: en Cristo, en la cruz, en la Eucaristía. No es solo intuición estética: es encuentro real.

- Finalmente, ella no separa razón y fe. Muestra que las vías de Santo Tomás son verdaderas, pero sólo llegan a su plenitud cuando el Ser eterno se revela como persona: Dios-Amor. Ahí, lo que la razón descubre, la fe lo abraza. Y lo que Hölderlin llora como pérdida, la mística carmelita lo vive como Presencia.

Para decirlo en voz alta o usar en video

“Santo Tomás demuestra con la razón que Dios existe. Edith Stein demuestra con la vida que ese Dios puede ser encontrado. Y mientras Hölderlin canta el dolor del Dios ausente, Edith Stein contempla el rostro del Dios vivo. Las cinco vías son el camino del alma que no se conforma con el cambio, la causa o el orden… sino que se lanza hacia el Ser eterno, que no es una idea, sino una Persona que ama.”

English

The 5 Ways of Saint Thomas Aquinas for Dummies

Saint Thomas proposes five paths to demonstrate that God exists—not starting from faith, but from reason. These five ways are found in his Summa Theologica and are based on what we can all observe in the world. They are not mathematical proofs, but philosophical, inductive arguments that move from experience to the ultimate Principle.

1. The Way of Motion (or Change)

Everything that moves is moved by something else.

Example: a stone moves because someone throws it.

But we cannot have an infinite chain of movers.

There must be a First Unmoved Mover: that is God.

2. The Way of Efficient Cause

Nothing causes itself.

Example: a flower comes from a seed, which comes from another flower, and so on.

But there cannot be an infinite chain of causes.

There must be a First Cause that is itself uncaused: that is God.

3. The Way of Contingency and Necessity

Everything that exists could have not existed—it is contingent.

But if everything were contingent, at some point, nothing would have existed.

There must be a Necessary Being that gives existence to all else: that is God.

4. The Way of Gradation (Degrees of Perfection)

We see things that are good, better, more beautiful, more just…

And we measure these degrees by comparing them to a maximum.

There must be a being who is the maximum of Goodness, Beauty, and Truth: that is God.

5. The Way of Design (Teleological Argument)

Non-intelligent things (like the sun, DNA, or instinct) act with order.

That order cannot come from chance.

There must be a supreme intelligence that directs all things toward an end: that is God.

What does Edith Stein do with these five ways?

Edith Stein, a disciple of Husserl, enters into dialogue with Saint Thomas in a phenomenological, existential, and mystical key. In her work Finite and Eternal Being, she does not simply repeat the five ways—she internalizes them, deepens them, and crosses them with her search for the Absolute Being.

She takes seriously the limits of modern thought: it is no longer enough to prove God as the “Unmoved Mover.” The human being seeks more than a Cause—he or she seeks meaning, fullness, being in its profoundest sense.

She deepens the third way (contingent-necessary):

For Stein, the contingent being—ourselves—cannot sustain itself.

We need to participate in a Being that is the fullness of being, what she calls the Eternal Being. And that Being is not just pure act: it is personal Love, communicative plenitude.

From the fifth way (order and finality), she discovers intentionality:

The world has meaning because it is ordered toward something, and human consciousness itself seeks direction. She links this to the dynamism of grace and the vocation of the soul. There is not only cosmic order—there is an existential orientation toward the Absolute.

She contrasts this with the poetic vision of Hölderlin, who sings of the nostalgia for the Absolute but cannot affirm it. In Hölderlin, God is absence, rupture, unreachable beauty.

For Stein, by contrast, the Eternal Being reveals itself: in Christ, in the cross, in the Eucharist. It is not just aesthetic intuition—it is a real encounter.

Finally, she does not separate reason from faith. She shows that Saint Thomas’s ways are true, but they reach their fullness only when the Eternal Being reveals Himself as a person: God-Love. There, what reason discovers, faith embraces.

And what Hölderlin mourns as loss, the Carmelite mystic lives as Presence.

A powerful voiceover use:

“Saint Thomas proves through reason that God exists.

Edith Stein proves through her life that this God can be found.

And while Hölderlin sings the sorrow of an absent God,

Edith Stein contemplates the face of the living God.

The five ways are the path of the soul that refuses to settle for motion, causality, or order…

and instead leaps toward the Eternal Being—who is not an idea, but a Person who loves.”

Leave a comment