Israel Centeno

El selfie de Dios y la victoria del Ser

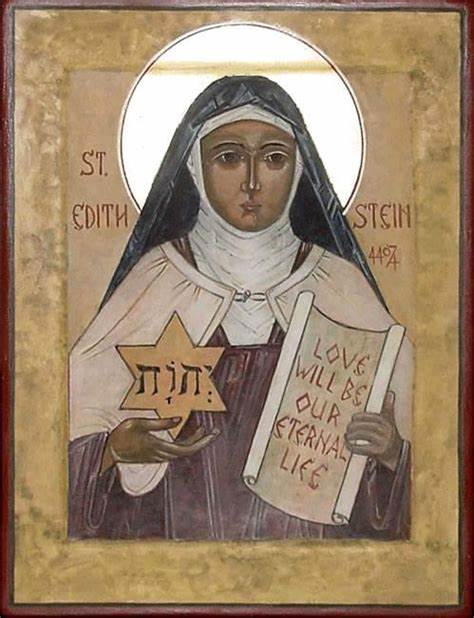

Las cinco vías de Santo Tomás, el dolor según Edith Stein, el libre albedrío y la luz que no quema

Santo Tomás de Aquino propuso hace más de 700 años cinco vías para llegar a Dios usando solo la razón. No la Biblia, no la fe, no una experiencia mística. Solo la observación del mundo, el pensamiento ordenado y el deseo de comprender por qué hay algo y no más bien nada.

Decía: todo lo que se mueve es movido por otro. Toda causa tiene una causa anterior. Lo que existe, pudo no haber existido. Lo que tiene grados, se compara con un máximo. Y lo que actúa sin inteligencia, lo hace por una inteligencia superior. Todas estas observaciones nos llevan —si pensamos bien— a un Primer Motor, una Causa No Causada, un Ser Necesario, una Perfección Suprema, una Inteligencia Ordenadora. A eso, Santo Tomás le llama Dios.

Y sin embargo, la razón más pura tropieza siempre con la pregunta más antigua: ¿Y el mal?

Si ese Dios es bueno, ¿por qué permite que suframos? Si es todopoderoso, ¿por qué no detiene el dolor, la injusticia, la enfermedad, la guerra, la soledad?

Ese es el problema más difícil, y Santo Tomás no lo evade. Lo enfrenta. Y responde diciendo que Dios permite el mal para sacar de él un bien mayor. Que el mal no es creado por Dios, sino permitido por su libertad infinita, y que el bien del universo entero, visto en su totalidad, es mayor que la suma de sus partes rotas. Que el mal tiene sentido solo desde la eternidad.

Pero eso, dicho desde una cátedra, puede sonar frío.

Edith Stein —la filósofa judía que se convirtió al cristianismo, se hizo carmelita, y murió en Auschwitz— no responde desde un aula, sino desde la cruz. Ella no niega el mal. Lo mira de frente. Lo sufre. Lo atraviesa. Y sin embargo, no desespera. Porque para ella, como para Tomás, el mal no es el final del argumento, sino la antesala de un encuentro.

En su obra La Ciencia de la Cruz, Stein no ofrece una teoría del mal: ofrece una participación. Ella entiende que el único modo de comprender por qué Dios permite el sufrimiento, es mirar a Cristo crucificado. El Ser eterno —ese que Tomás deduce y que la filosofía moderna desdibuja— se deja clavar en un madero. El Dios que es puro acto se deja inmovilizar. El que es causa primera se hace efecto último. El que es belleza infinita, se deja deformar.

Ahí, en ese escándalo de amor sin límite, Edith Stein encuentra su respuesta.

Y allí también, donde Hölderlin ve sólo nostalgia de un Dios perdido, Edith ve una Presencia ardiente. Hölderlin canta al Absoluto inalcanzable, al Dios que abandonó a los hombres. Edith, en cambio, entra en el Carmelo y abraza la Cruz: no porque la entienda del todo, sino porque sabe que el amor tiene razones que solo la cruz puede enseñar.

Las cinco vías de Tomás te llevan hasta el umbral. Hasta el Ser que no cambia, que no muere, que no depende de nadie. Edith Stein cruza ese umbral: y encuentra no una idea, sino un rostro. Un rostro herido. Un rostro que sangra con nosotros. Un rostro que no explica el mal, pero que lo redime desde dentro.

Entonces, tal vez la pregunta ya no sea: ¿por qué Dios permite el mal? Sino: ¿por qué un Dios que no necesita nada decidió cargarlo sobre sus hombros?

¿Por qué, pudiendo quedarse en la perfección intocable del Ser eterno, eligió hacerse carne en un mundo quebrado?

Y allí entra otro misterio: la libertad.

Dios creó al ser humano con libre albedrío, incluso sabiendo que esa libertad sería usada para hacer el mal. Y no solo eso: nos colocó en una naturaleza hostil, con terremotos, enfermedades, envejecimiento, muerte. ¿Por qué? Porque sin libertad, no hay amor. Y sin un mundo real, donde el bien y el mal tengan consecuencias, no hay virtud. La hostilidad de la naturaleza, el límite de la carne, no son castigos, sino escenarios: el teatro donde se libra la batalla por la esperanza, la caridad, la fidelidad, la entrega.

No hay filosofía que lo resuelva. Solo una respuesta, que Santo Tomás, Edith Stein y los mártires de todos los tiempos han repetido: por amor. Y ese amor no se prueba en silogismos. Se prueba en la Cruz.

Por eso, tras recorrer las vías de Santo Tomás y atravesar con Edith Stein el abismo del mal, queda una verdad luminosa y definitiva: Santo Tomás nos enseña a identificar a Dios. Edith Stein nos enseña a llamarlo por su nombre.

Tomás lo descubre como Acto Puro, como Ser necesario, como Fundamento último del universo. Y ese descubrimiento, hecho con la razón, es ya un acto de fe racional.

Pero Edith —que ha pasado por el dolor del exilio, la pérdida, la noche del alma— se atreve a pronunciar ese nombre escondido desde toda la eternidad: Jesucristo.

Donde la razón lo alcanza, el amor lo abraza. Donde la filosofía lo reconoce, la cruz lo revela. Donde los pensadores callan, la mártir susurra: “Él está aquí.”

Porque el Ser que Santo Tomás definió con la precisión del sabio, es el mismo que se dejó clavar por amor, que venció a la muerte, y que sigue viviendo en cada alma que lo llama por su nombre.

Y como coda final, tal vez la clave no esté en una prueba racional ni en una refutación moderna. Tal vez estuvo desde el principio, en el libro más antiguo de todos. En Job. Aquel hombre justo que no entendía por qué sufría, que perdió todo, que discutió con Dios… y que al final, no recibió una explicación, sino una Presencia. “Te conocía sólo de oídas —dijo—, pero ahora te han visto mis ojos.”

Esa es la respuesta definitiva: no una fórmula, sino un rostro. El rostro de Aquel que venció el mal, no anulándolo, sino habitándolo desde dentro. Ese rostro, que quedó impreso en una sábana, es el mismo que Job intuyó en el torbellino: el del Dios que no responde desde lejos, sino desde dentro del dolor. El Dios que, al final, no se explica. Se muestra.

Ensayo Dios Tomas Stein

PLUS

God’s Selfie and the Victory of Being

The Five Ways of Thomas Aquinas, the Suffering According to Edith Stein, Free Will, and the Light That Does Not Burn

Over 700 years ago, Thomas Aquinas proposed five ways to reach God using reason alone. Not the Bible, not faith, not mystical experience—just observation of the world, ordered thinking, and the desire to understand why there is something rather than nothing.

He said: everything that moves is moved by another. Every cause has a preceding cause. Everything that exists could have not existed. All gradations are measured against a maximum. And things without intelligence act toward an end only if guided by intelligence. All these observations lead—if we think well—to a Prime Mover, an Uncaused Cause, a Necessary Being, a Supreme Perfection, an Ordering Intelligence. To this, Aquinas gives the name God.

And yet, the purest reason always stumbles upon the oldest question: What about evil?

If this God is good, why does He allow suffering? If He is all-powerful, why doesn’t He stop pain, injustice, sickness, war, loneliness?

This is the hardest problem, and Thomas does not evade it. He faces it. He answers that God allows evil to bring about a greater good. That evil is not created by God, but permitted by His infinite freedom. That the good of the universe as a whole, seen from eternity, is greater than the sum of its broken parts. That evil only makes sense from the perspective of the eternal.

But said from a lectern, that can sound cold.

Edith Stein—the Jewish philosopher who converted to Christianity, became a Carmelite, and died in Auschwitz—does not respond from a classroom, but from the cross. She does not deny evil. She looks it in the face. She suffers it. She walks through it. And yet, she does not despair. Because for her, as for Thomas, evil is not the end of the argument but the threshold of an encounter.

In her work The Science of the Cross, Stein offers not a theory of evil, but a participation in it. She understands that the only way to grasp why God allows suffering is to gaze upon the crucified Christ. The Eternal Being—the one Thomas deduces and modern philosophy obscures—allows Himself to be nailed to wood. The God who is Pure Act becomes immobilized. The First Cause becomes the final effect. Infinite Beauty allows itself to be deformed.

There, in that scandal of limitless love, Edith Stein finds her answer.

And there too, where Hölderlin sees only the nostalgia of a lost God, Edith sees a burning Presence. Hölderlin sings to the unreachable Absolute, the God who abandoned humanity. Edith, by contrast, enters Carmel and embraces the Cross—not because she understands it fully, but because she knows that love has reasons only the cross can teach.

The five ways of Thomas lead you to the threshold. To the Being who does not change, does not die, does not depend on anything. Edith Stein crosses that threshold—and finds not an idea, but a face. A wounded face. A face that bleeds with us. A face that does not explain evil but redeems it from within.

Then perhaps the question is no longer: Why does God allow evil? But rather: Why would a God who needs nothing choose to carry it on His shoulders?

Why, when He could have remained in the untouchable perfection of eternal Being, did He choose to become flesh in a broken world?

And here enters another mystery: freedom.

God created humans with free will, even knowing that this freedom would be used to commit evil. And not only that: He placed us in a hostile nature, with earthquakes, illness, aging, and death. Why? Because without freedom, there is no love. And without a real world, where good and evil have consequences, there is no virtue. The hostility of nature, the limitations of the flesh, are not punishments but settings: the stage where the drama of hope, charity, fidelity, and sacrifice is played out.

No philosophy can solve it. Only one answer remains, the same one that Thomas, Edith Stein, and the martyrs of every age have repeated: For love. And that love is not proven in syllogisms. It is proven on the Cross.

So, after walking the paths of Thomas Aquinas and descending with Edith Stein into the abyss of evil, one luminous and definitive truth remains: Thomas Aquinas teaches us to identify God. Edith Stein teaches us to call Him by His name.

Thomas discovers Him as Pure Act, as Necessary Being, as the Ultimate Ground of the universe. And that discovery, made through reason, is already an act of rational faith.

But Edith—who walked through exile, loss, and the night of the soul—dares to speak the name hidden from all eternity: Jesus Christ.

Where reason reaches, love embraces. Where philosophy recognizes, the cross reveals. Where thinkers fall silent, the martyr whispers: “He is here.”

For the Being Thomas defined with the precision of a sage, is the same who allowed Himself to be nailed for love, who conquered death, and who lives still in every soul that calls upon His name.

And as a final coda, perhaps the key lies not in rational proof or modern refutation. Perhaps it has been there from the beginning, in the oldest book of all: Job. That just man who did not understand why he suffered, who lost everything, who argued with God… and who, in the end, received not an explanation, but a Presence. “I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear,” he said, “but now my eyes see you.”

That is the ultimate answer: not a formula, but a face.

The face of the One who conquered evil not by erasing it, but by dwelling within it.

That face, imprinted on a shroud, is the same one Job sensed in the whirlwind:

the God who does not respond from afar,

but from within the pain.

The God who, in the end,

does not explain. He reveals.

Leave a comment