From Epic to Ideological Smoothie

Israel Centeno

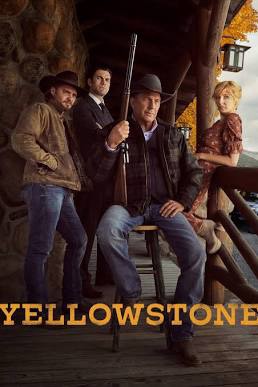

Yellowstone arrived as the definitive Western of the 21st century. A family saga, territorial, raw. Land, horses, rifles, blood, legacy. In its early iterations—1883 and 1923—it seemed to resurrect that narrative voice Hollywood had buried under superhero franchises. The West was back, they said, and it had grit. But what began as epic tragedy ended as a soap opera in a Stetson.

Those first two prequels have what most current series lack: narrative gravity. In 1883, we witness the brutality of the westward march as a dance of death, ambition, and promise. No sermons. No apologies. Everything burns. Native peoples are treated with respect, but not through progressive pamphleteering—they are portrayed historically. Neither exotic victims nor ecological sages, but peoples facing their own tragedy.

In 1923, capitalism is no longer a dream but a ditch. The Dutton ranch resists emerging predators: bankers, corporations, and that eternal figure—the freshly-arrived rich man in a three-piece suit and the soul of a foreclosure lawyer. The conflict widens, but it doesn’t dilute. The story asserts itself. The viewer understands without being lectured. The script trusts its audience.

And then, as often happens with modern sagas, the present ruins the past. Yellowstone, with Kevin Costner at the helm, becomes a series unsure if it wants to be The Sopranos on horseback or an emotional guidebook for Midwest trauma survivors, filmed by National Geographic.

At times, it feels inspirational: the stoic cowboy, the wild daughter, the traumatized grandson, the wise Native elder, the land as sacred inheritance. But then come the speeches, the glances into camera, the forced woke insertions, the absurd soap opera arcs. One no longer knows if they’re watching a Western or a muscular version of This Is Us—with saddles and cheap whiskey.

The show tries to defend private property, critique extractivism, condemn tourism, glorify legacy, include Indigenous trauma, promote diversity, and maintain a country-club aesthetic with issues. It’s as if a team of progressive writers and another of ultra-conservatives sat in the same room with one rule: don’t delete anything. The result: a narrative smoothie.

Once, land was just land. You farmed it, defended it, inherited it. Now it’s a metaphor: for identity, soul, guilt, privilege, collective trauma, lost posterity. The viewer no longer knows whether to root for the Duttons, the Natives, the State, the corporations, or the bears.

Land is no longer fought over—it’s performed. The characters don’t live on it—they interpret it. The ranch becomes a symbol of everything and nothing. And in the process, the Western loses its soul: that unique power to show conflict without turning it into a speech.

What began as a silent epic ends as a Netflix roundtable. Yellowstone tries to say it all and ends up saying very little. There’s no room left for dust or silence. Everything is explained. Everything narrated. Everything felt.

Is it bad? No. It’s worse: it’s expensive confusion. And therein lies its tragedy.

What was once great now doubts its own greatness. What was once epic now apologizes. The cowboy no longer rides off into the sunset—he signs institutional press releases from the ranch

Leave a comment