Israel Centeno

There are writers whose work seems destined to remain at the margins, not because of any deficiency, but because their very rigor, their refusal to surrender to the fashions or comforts of their time, demands from readers a rare and exacting attention.

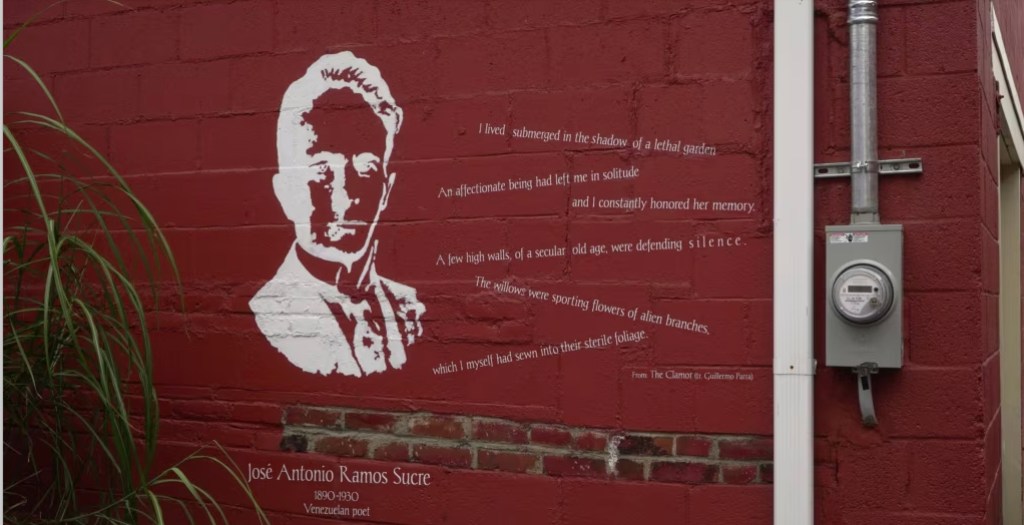

José Antonio Ramos Sucre belongs to that lineage.

Often misunderstood, occasionally misused by political and literary factions, his work persists beyond those ephemeral appropriations.

It does so because it is built on foundations deeper than circumstance:

on the refusal of false consolation, on the lucidity of exposed existence, on the severe beauty of a language carved against forgetting.

This essay is not an attempt to frame Ramos Sucre within the usual historical categories, nor to reduce him to a biographical anecdote.

It is a meditation on his stature as a classical and pagan poet, a sentinel of the night who did not expect redemption yet insisted on the dignity of form, on the necessity of naming even when language itself seemed to collapse.

Throughout these pages, we have sought to restore Ramos Sucre to the dimension that truly belongs to him:

neither the misunderstood martyr nor the nationalist symbol, but the solitary craftsman of a literature that stands, still today, like a pure mineral against the erosion of time.

Readers wishing to approach his work in English will find a valuable entry point in the translations offered by Guillermo Parra, whose careful efforts have begun to reveal, beyond linguistic barriers, the depth and precision of a poet who remains a secret yet to be fully explored.

To read Ramos Sucre is to walk alongside a consciousness that chose to remain awake amid a humanity lulled by its own fictions.

It is to recognize, perhaps with a shudder, the fragile but enduring fire that persists in the heart of those who refuse to forget the darkness.

José Antonio Ramos Sucre was not a martyr of sensitivity nor a spectral figure trapped in the malaise of his century.

He was, above all, a classical and pagan poet, possessed of an aesthetic conscience that admitted no concessions.

That his life was marked by insomnia, solitude, and the quiet erosion of existence should not be read as biographical accident or sentimental excuse: it is the necessary condition for understanding his literary rigor, his distrust of facile narratives, his devotion to the extreme precision of language.

His figure, however, has been mistreated by certain postmodern readings which, anxious for victims and fractures, have sought to reduce his work to mere testimony of suffering, an echo of pathology.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Ramos Sucre did not write from the wound; he wrote from a lucidity that did not need to exhibit itself as pain.

His poetry, his fragmentary prose, his worlds of weary heroes and crumbling cities, do not spring from a desire for self-pity, but from an exact —and therefore merciless— vision of the inevitable decline of forms, cultures, and bodies.

His gaze is that of the pagan who expects no redemption, yet persists in seeking, through form, rhythm, and the precise tone, a secret resistance against disintegration.

This essay —this rereading— emerges from the need to restore Ramos Sucre to his real stature:

that of a poet who, like the ancients, understood that human life is brief, tragic, and worthy, and that the only possible response to its precariousness is the severe beauty of a well-achieved form.

The shadowed house where he grew up, the silences that wove his childhood, the insomnia that carved his perpetual wakefulness, the early suspicion that power corrupts even memory itself —these are not mere biographical details that “explain” or “justify” his work; they sharpen it.

It is not about psychologizing him, redeeming him, or turning him into the emblem of any contemporary cause.

It is about reading him for what he truly was:

a builder of verbal labyrinths, a forger of apocryphal memories, a solitary watchman who, at the brink of collapse, chose beauty as his only form of resistance.

This reading, therefore, refuses to mourn him.

It chooses instead to accompany him in his task:

to name, with the precision of one who knows time is an enemy and not an ally, the still-living ruins of the human.

The Shadowed House —

Childhood, Silence, and the Architecture of Exile

José Antonio Ramos Sucre’s childhood cannot be reduced to the anecdote of a distant province or to the sentimental postcard of a sleepy colonial town.

For him, Cumaná was neither a founding myth nor a landscape to be celebrated: it was the origin of an early estrangement, the laboratory of an inner exile that would mark his entire body of work.

The house where he grew up does not appear in his writing as an emblem of belonging, but as the first space of alienation.

Rather than shelter, it was confinement.

Rather than root, it was labyrinth.

Ramos Sucre was born into a decaying illustrious lineage, a family that carried in its decline an implacable nostalgia for a past that no longer existed.

The architecture of that house —its endless corridors, its sun-scorched patios, its rooms with closed doors— is inseparable from his emotional education:

an early lesson in enclosure, echo, and emptiness.

Family life, governed more by silences than by affections, instilled in his temperament an irreparable distrust of human ties.

The severe authority of his uncle —whose figure can be intuited as both oppressive and ominous— did not merely fracture his relationship with the immediate world: it planted in him the fundamental intuition that all power, even in its most intimate forms, is a degradation of the soul.

Yet Ramos Sucre did not transform that first exile into denunciation or drama.

He sublimated it into aesthetics.

The exile of his childhood did not lead him to sentimental confession, but to the construction of a poetics of estrangement, where every phrase, every fragment, every scene bears the mark of someone who never truly had a home.

The shadowed house of Cumaná is not merely a biographical memory: it is the mental architecture of his literature.

His prose poems —meticulous, austere, spectral— are sealed rooms, corridors without exit, patios where time seems suspended.

Each of his texts repeats, in veiled form, the same experience: that of the child wandering alone through a house too large, conscious that every promise of refuge is a lie.

From this rupture with the natural world of childhood, Ramos Sucre accessed a radical modernity that should not be confused with the simple adoption of new techniques.

His modernity lies in his refusal to accept the fiction of a repairable order.

Where others sought to celebrate nation, civilization, or progress, he offered the map of an original loss, anterior to all collective history, anterior even to political consciousness itself.

Estrangement for Ramos Sucre was not an accident of fate; it was his only true homeland.

Thus, his literature does not belong entirely to any time, any language, any tradition capable of appropriating him.

His lineage is that of the insomniacs, the wanderers, those who, even surrounded by familiar walls, know they will never truly return to the house of childhood.

That knowledge —serene, bitter, irreparable— is what gives his work its unique gravity.

And it is also what makes him, despite the efforts of those who would tame him within the cages of modernism or literary victimhood, one of the few genuine classics produced by the Spanish language in the Americas.

From the shadowed corridors of his natal house, Ramos Sucre was already gazing toward that place where no comfort, no belonging, is ever truly possible:

the precise place from which he continues to speak to us.

The Uncle’s Shadow — Abuse, Trauma, and Literary Transfiguration

Among the silent figures populating José Antonio Ramos Sucre’s intimate universe, the uncle —omnipresent in his unofficial biography— holds a decisive place.

Not as a character, not as anecdote, but as a dark force that, without being explicitly named in his work, shapes much of his relation to the world.

The shadow of the uncle needs no lurid illumination.

Its weight is measured in its effects: a radical distrust of all authority, an almost absolute withdrawal in his human relations, a persistent sense of danger that permeates even his briefest texts, and the conviction that every presence, once too close, becomes a threat.

Violence —more psychic than physical, though not necessarily devoid of corporal brutality— marked his understanding of human bonds as networks of domination rather than mutual support.

Yet, true to his rigor, Ramos Sucre never turned his biography into confessional material.

There are no laments in his writing, no catharsis, no acts of revenge.

The wound becomes form.

Pain, transfigured into language, detaches itself from autobiography to become aesthetic experience.

His literature is born precisely where trauma neither demands pity nor offers testimony, but where it is elaborated into a structure of perception and a method of world-making.

In Las formas del fuego, in El cielo de esmalte, in La torre de Timón, the figures populating his fragments do not trust, do not surrender, do not return.

They wander through indifferent or hostile spaces, persisting in their journey without expecting redemption.

They are the heirs of the poet’s earliest experience: inhabiting a space that, instead of sheltering, annihilated; that, instead of protecting, devoured.

This literary transfiguration of trauma is evident in several key formal choices:

fragmentation as a resistance to the closure of grand narratives;

the preference for prose poetry as a way to speak without surrendering to easy lyricism;

an extreme economy of language, where every word seems chosen to betray no illusions.

The abuse is not thematized; it is absorbed into the deep structure of his vision.

Every narrative is suspect.

Every community is illusory.

Every promise of belonging, a trap.

Understood this way, Ramos Sucre’s project is not merely aesthetic: it is ontological.

To name the world, for him, is to acknowledge its original corruption.

The word does not save; it merely salvages, at best, a few fragments of dignity.

This is why Ramos Sucre’s work does not age, nor does it lend itself easily to the readings that seek to turn him into an exemplary victim or an unwitting precursor of literary trends.

His formal severity, his tragic conception of human bonds, and his ethics of distance place him within a stricter lineage:

that of writers who, without denying the wound, refuse to let the wound dictate the form.

The uncle’s shadow, in this sense, is not merely a biographical detail.

It is the living metaphor of all power that corrupts.

And it is also the secret source of a literature that, in rejecting falseness and facile consolation, achieves a greatness few have managed without falling into cynicism or despair.

Ramos Sucre bore that tension —and transformed it into language— until the very last instant of his endless vigil.

In Writing Against the Night

It is no minor detail that José Antonio Ramos Sucre, in several letters, confessed to chronic insomnia.

It was not a passing disorder, but a constitutive condition of his existence.

For him, the night was not the time of rest but the time of truth: the space where consciousness, stripped of the consolations of ordinary wakefulness, confronted its essential nakedness.

Yet Ramos Sucre never turned his insomnia into sentimental material.

There is no exaltation of suffering in his work, no indulgence in wretchedness.

Insomnia, more than an ailment, is the starting point of an exacting aesthetic:

an aesthetic that rejects the comfort of continuous narration, distrusts the logic of closed stories, and knows that human experience, in its deepest core, is fragmentary, discontinuous, erratic.

Hence his choice of prose poetry: not as a gratuitous formal innovation, but as the form best suited to a mind that could neither sleep nor deceive itself.

The linearity of traditional verse, the soothing musicality of rhyme, were incompatible with the merciless clarity of one who could not rest even in dreams.

For Ramos Sucre, writing was a way of resisting collapse:

a way of keeping consciousness active against the decomposition of meaning, against the erosion of memory, against the impossibility of reconciling with the world.

The insomniac night is not merely a theme in his work: it is its natural atmosphere.

Each of his fragments is tinged by that vigil:

the vigil of one who knows every consolation is a form of self-deception;

the vigil of one who walks among ruins no one attempts to rebuild;

the vigil of one who writes because, without writing, he would be devoured by emptiness.

This extreme tension translates into a fierce economy of language.

There is no superfluous adornment or ornamental gesture in Ramos Sucre.

Each word is weighed, measured, inscribed as if it were the last.

Each image arises not to embellish the void but to name it with the greatest possible precision.

Insomnia, therefore, not only marks his biography: it structures his entire work.

It shapes his style, his sense of time, his conception of the human condition.

For the one who does not sleep, the world reveals its true fragility:

cities are precarious fictions, institutions are masks for underlying violence, affections are brief truces against exposure.

Thus, his work offers no redemption.

It offers no escape or consolation.

It does not seek to redeem suffering but to assume it, to transfigure it into the only resistant material available: form.

In a world that promised modernity, progress, and civilization, Ramos Sucre chose to remain awake:

a man fully conscious amid a humanity asleep in the comfort of broken promises.

His insomnia was neither an illness nor an accident:

it was the price and the condition of his lucidity.

And it was, too, the crucible where his texts were forged —those hard and pure fragments that, even today, unlike most literary gestures, resist oblivion, misunderstanding, and the erosion of meaning.

Writing against the night was not, for Ramos Sucre, a heroic or romantic gesture.

It was an act of extreme necessity:

the necessity of not disappearing without leaving, at least, a faithful trace of the vast exposure.

The Inner Exile — Cumaná, Caracas, Geneva

José Antonio Ramos Sucre’s movement across different cities cannot be interpreted through the traditional lens of travel as expansion or worldly conquest.

His displacements were, in essence, a continuation of his inner exile: a mere change of scenery for a condition that never abandoned him.

Neither Cumaná, nor Caracas, nor Geneva offered the promise of reconciliation.

In every place, Ramos Sucre remained a foreigner.

Cumaná was not his root, but his first frontier.

The city that in other writers might have inspired solar mythologies left in him the mark of essential orphanhood.

Nothing of the colonial landscape, nothing of familial warmth, succeeded in founding an affirmative identity within his sensibility.

Cumaná was, for Ramos Sucre, the foundational experience of enclosure and estrangement.

Caracas, the ascendant capital, did not offer a more welcoming homeland.

The fragmentary modernization of the country under the Gómez regime, the hardening of institutions, the vulgarity of public life, only heightened his sense of displacement.

The bureaucratic life he endured in Caracas was mere survival:

a means of maintaining material existence while his inner life unfolded in a graver, more remote dimension.

Geneva, at last, far from representing the scene of redemption or liberation, became the clearest mirror of his radical estrangement.

The geographical distance from his country did not heal his sense of isolation: it deepened it.

His correspondence from Geneva reveals a man exhausted, lucid to the limit, fully conscious that no spatial distance can redeem a fracture that is, above all, spiritual.

Amid the silent murals of Sampsonia Way in Pittsburgh —a street once home to exiled writers under the shelter of City of Asylum— one senses the faint, unbroken thread that links José Antonio Ramos Sucre to all those who have written from displacement.

Though Ramos Sucre never walked these streets, his spirit inhabits them: a consciousness exiled not only from nations but from the very illusions of belonging.

Like the faces painted on the walls of Sampsonia, his work stands against the erosion of memory, against the easy reconciliations of history.

In a world that still invents borders to contain what cannot be contained —language, imagination, solitude— Ramos Sucre remains a secret sentinel, guarding the last territory that no exile can surrender: the dignity of the lucid word.

His suicide should not be interpreted as a romantic failure or a gesture of literary despair.

It was the logical conclusion of a life lived under the extreme tension of one who never accepted the fictions of consolation.

In a world offering false belongings, Ramos Sucre chose the final coherence of rejecting all simulacra of reconciliation.

Ramos Sucre’s exile was not a consequence of external circumstances.

It was his ontological state.

From childhood, from the shadowed corridors of his natal house, he understood there would be no possible homecoming.

There is no nostalgia for a lost homeland in his work: only the certainty that estrangement is the true human condition for the lucid.

Thus, his literature offers no roadmaps for return, no songs of longing.

His texts are minimal monuments to exposure:

verbal structures carved to resist disintegration, to signal, amid the collapse of cultures and affections, the possibility of a form that —though precarious— does not betray the gravity of existence.

In his passage from Cumaná to Caracas, and from Caracas to Geneva, Ramos Sucre did not alter his condition: he refined it, he purified it, until reaching its most rigorous expression:

a man utterly alone, utterly lucid, who made of his estrangement not a theme, but a method.

An exile without return.

A vigil without dawn.

A literature without sentimentality, without hope.

Such is, and remains, the true stature of José Antonio Ramos Sucre.

A Sentinel in the Night of the World

José Antonio Ramos Sucre cannot be justly understood through the terms of a literary history constructed on false oppositions.

For years, some attempted to counterpose him to Andrés Eloy Blanco, fabricating a fictitious antinomy: the popular, luminous poet, beloved of the masses, against the dark, hermetic poet, cloistered in his inner exiles.

It was a clumsy effort to use Ramos Sucre as a pawn in a political maneuver, a strategy to divide waters where no real conflict existed.

The operation failed.

Not for lack of propaganda, but because Ramos Sucre’s own aesthetics —his rigor, his gravity, his refusal to be instrumentalized— dismantled any attempt at manipulation.

His work, closed upon itself like a precisely carved stone, could not be turned into the banner of any circumstantial cause.

It belonged neither to popular singing nor to academic elitism.

It spoke in the name of no one but the solitary consciousness standing exposed before the void.

The difference between Ramos Sucre and Andrés Eloy Blanco lies not in intrinsic value —each pursued distinct aesthetic necessities— but in the radical divergence of their poetic projects.

Blanco remains a poet of communion, of human suffering shared.

Ramos Sucre, by contrast, chose the extreme solitude of one who expects no reconciliation.

In his writing, there is no “we” from which to speak: only an “I” that knows every community is a momentary fiction.

His vigilance, his insomnia, his estrangement, are not rhetorical gestures: they are his being.

And in that inflexible fidelity to his vision lies his greatness.

Ramos Sucre does not offer consolation, does not celebrate identities, does not invent heroic genealogies.

He named, with the precision of one who permits no illusions, the disintegration of memory, the exposure of being, the ultimate fragility of every human project.

Today, his voice persists.

Not as an echo of pain, but as a silent sentinel that continues to illuminate the night for those unwilling —or unable— to sleep in the comfort of easy fictions.

A presence that, at the brink of the abyss, refused to close its eyes.

Ramos Sucre remains there, where he always was:

in the sleepless vigil, in the unreconciled memory, in the minimal fire that, against all odds, still burns.

For those who wish to read Ramos Sucre directly in English, there is a notable translation by Guillermo Parra, offering access to the depth and resonance of a poet who remains, even today, a secret waiting to be fully encountered. Ramos Sucre Elegy for a Silent Homeland

Leave a comment