The Tower of Alexandria

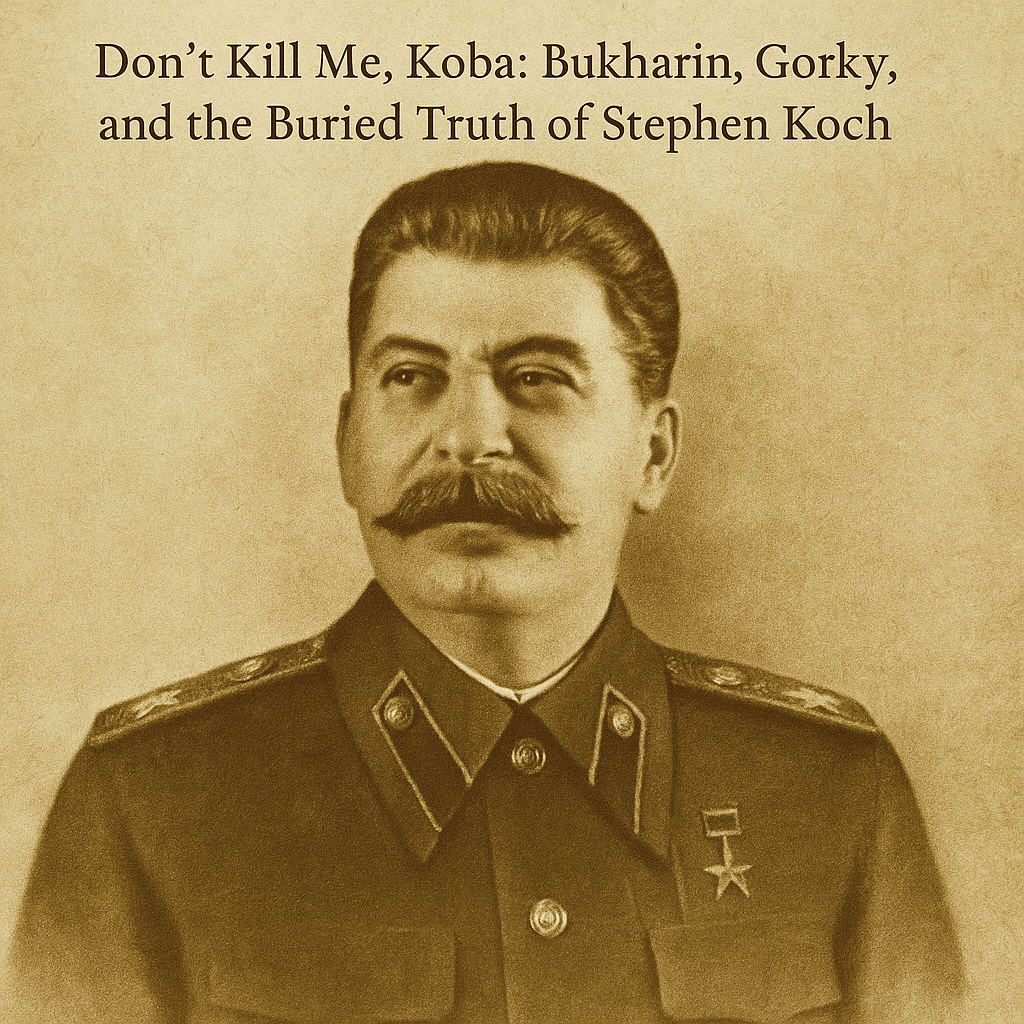

Don’t Kill Me, Koba is a literary and historical reflection on the tragic returns of Bukharin and Gorky to Stalin’s Soviet Union—and the forgotten American author who told their story with unmatched clarity: Stephen Koch. Why was he erased? Why was his work plundered? This essay connects erased martyrs with silenced writers, revealing the machinery of curated forgetting in both totalitarian regimes and modern cultural institutions.

By Israel Centeno

“Don’t kill me, Koba.”

That was Nikolai Bukharin’s final plea before his execution. He didn’t cry “Long live the Party!” or “Down with fascism!” He simply begged. He used Stalin’s intimate nickname—Koba—as if pleading with a treacherous father, as if realizing, too late, that the god he had served was false.

That phrase—small, broken, desperate—encapsulates not just the tragedy of the 20th century, but the seduction and betrayal of intellectuals under totalitarian power.

Few have had the courage to tell that story with the precision and clarity of Stephen Koch, an American novelist, historian, and inconvenient witness. But before we turn to him, we must return to the origin.

Nikolai Bukharin could have stayed in Paris. In 1936, he was there negotiating the acquisition of the Marx and Engels archives. He knew what was happening back in Moscow. The purges. The show trials. The confessions scripted like operas of guilt. He knew Kamenev and Zinoviev had already swallowed their own names. He knew exile could mean survival.

And yet—he returned.

He returned knowing.

Was it loyalty? Blind faith in the Party? A doomed hope for Stalin’s mercy? Or the unbearable weight of abandoning the revolution that had shaped him? We’ll never fully know. But Bukharin came back. He was arrested, paraded in court, and made to confess to crimes he never committed. He was executed.

And his last words were: “Don’t kill me, Koba.”

Maxim Gorky also could have died abroad. Ailing, aging, world-famous. But in 1931 he returned to the USSR—not to write, but to be written into the narrative. He lived under surveillance. His son was arrested and died. His manuscripts were confiscated. His inner circle infiltrated.

He was dying already, but it wasn’t fast enough. According to several accounts, Gorky was poisoned. His secretary was a NKVD informant. His doctors were “removed.” And Stalin wrote the obituary.

Like Bukharin, Gorky returned knowing.

This is where Stephen Koch comes in—one of the very few who dared to narrate these stories with honesty. In Double Lives: Spies and Writers in the Secret Soviet War of Ideas Against the West, Koch exposed how the Soviet Union didn’t just build tanks. It built stories. Through Willi Münzenberg, the Soviets weaponized culture: magazines, manifestos, films, “peace congresses,” letters signed by fashionable authors.

Münzenberg didn’t need intellectuals to be communists. He just needed them to say the right things, wear the right mask, decorate the brutality with elegance.

Koch did not write with hatred. He wrote with surgical calm. And that’s why it hurts. Because he named names: Brecht, Aragon, Gide, Hemingway. He showed that the real war was fought not only on the frontlines but in universities, journals, and literary salons.

In The Breaking Point, Koch chronicled the split between Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos during the Spanish Civil War. Hemingway embraced the myth. Dos Passos saw too much—the bodies of anarchists, of Trotskyists, of his friends. And he broke ranks.

Hemingway became a statue. Dos Passos became a ghost.

Koch didn’t just tell their story. He revealed the anatomy of betrayal—when writers sacrifice truth for beauty, for ideology, or for acceptance.

But the most damning part of Koch’s legacy is not what he wrote—it’s how he was erased. There was no public rebuttal. No great intellectual duel. Just silence. He wasn’t banned. He was uninvited. Declared inconvenient. Too clear. Too factual. He said too much.

And worse: he was plagiarized.

Some sharp readers claim that the Spanish author of Sefarad borrowed whole themes, structures, even passages from Koch. That the pain of exile, the seduction of ideology, the betrayal of memory—so central to Koch’s work—were rebranded as postmodern fiction. That the theft was masked as homage.

In today’s literary world, that’s easy to do. You wrap someone else’s research in melancholy, fragment it into “novelistic freedom,” and win awards.

Meanwhile, the original author disappears.

The story repeats. Bukharin was erased with bullets. Gorky, with poison. Koch, with silence. All for the same reason: because they knew too much and tried to speak.

Today, no bullets are needed. Just exclusion. Just absence from catalogues. Just algorithms. Just grants that never arrive. A writer like Koch doesn’t die in a prison. He dies in footnotes no one reads.

And yet, his warning remains. His books remain. Hidden. Underrated. But true.

“Don’t kill me, Koba.”

That was Bukharin’s plea. But it could have been Koch’s too. Or Dos Passos’s. Or anyone who, facing the machinery of cultural politics, understood too late that truth has no lobby.

So we write this. From this imaginary tower. This minor Alexandria. To name the ones who knew. The ones who wouldn’t play along. The ones who were punished—not by censorship, but by curated forgetting.

Because as long as the archive breathes, Koba doesn’t win completely.

Israel Centeno

From the Tower of Alexandria, Year of the Buried Archive

Leave a comment