Israel Centeno

It’s Sunday. I went to Mass. I understand now why—from the priest to the middle-class woman to the homeless man—we all must recognize our guilt and ask for mercy. Speaking with David and reflecting on my life, I told him I had grown old without ever having killed a man. Then, in a deeper examination of conscience, I wondered whether I hadn’t killed through omission—within the framework of the great human tragedies, of all the horrors I’ve witnessed.

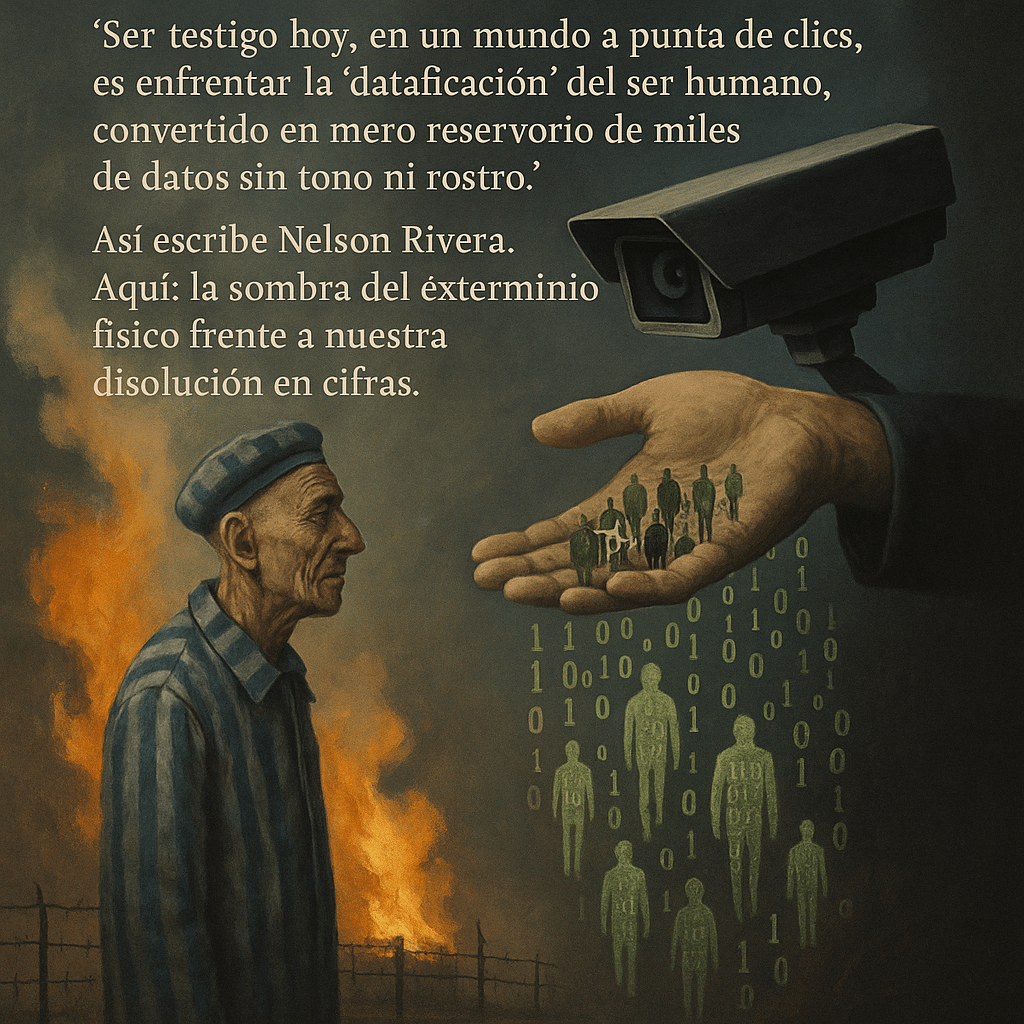

Today I understood, with a clarity that only spiritual maturity can offer, the meaning of original sin and the necessity of a savior. I understood why we are broken. Why goodwill and good ideas are not enough. I understood why Auschwitz did not end in 1945. Because its logic has mutated, and today it operates in subtler forms: the infrastructure of camps is no longer needed to perpetrate oblivion. It’s enough for a file to be deleted, a right denied, a story silenced. I understood this as I read Nelson Rivera’s passages where Auschwitz is not a place of the past but a language of the present: “the alphabet of the camp,” he writes, “has no commerce with life.” That alphabet—that apparatus of symbolic annihilation—bears an uncanny resemblance to the administrative language of our time: files, databases, algorithms. If yesterday arms were tattooed, today codes are assigned. If once we were destroyed by fire, now we are erased with clicks. I understood this not through drama, but through the moral precision of testimony. I understood that to be a witness today also means resisting this new form of disappearance: the digitalized, disposable soul. I understood that memory is not an intellectual pastime, but a moral obligation.

Reading the passages on the Armenian genocide and Auschwitz, a sharp pain presses on the chest. History repeats itself—not as farce, but as abyss. Armenia, Poland, Cambodia, Rwanda, Yugoslavia, Syria, Ukraine. More than one hundred million human beings in the 20th century, one by one, one after another, reduced to ashes by disproportion, by a will to annihilate that needs no reasons—only excuses. Auschwitz was not an episode; it was a fracture in modernity. A wound that still bleeds beneath the crust of our civilization. Auschwitz is the absence of God, or His silence, or His judgment. It is the end of language. The point where any explanation becomes obscene.

And yet, there are the witnesses. The voices. The books of Primo Levi, of Wiesel, of Antelme, of Semprún. These texts do not explain horror. They sustain it. They transmit it. They compel us to look. There is no philosophy that can match the moral power of those memories. No political theory can replace the testimony of a tortured body that writes, that remembers, that withholds forgiveness—not out of hate, but because forgiveness is not theirs to give.

Today I also read about Simone Veil. Her return to Auschwitz. Her firmness in saying: “No, I have never forgiven.” Not out of hatred, but out of respect. Because to collectively forgive such monstrosity would be to trivialize it. Veil understood that the commitment to memory requires more than reconciliation. It demands truth, testimony, and continuity.

And here I am, in Pittsburgh, trying to accompany that continuity. Thinking of extermination camps not as distant memory, but as a latent possibility in any society that idolizes power, eroticizes obedience, or aestheticizes violence. There are camps without barbed wire. There are exterminations that don’t smell of burnt flesh. There are silences that hurt just the same.

Today I also understood that my role is not that of a judge. It is that of a witness. And the witness is not neutral: the witness takes the side of the victim. The witness refuses to forget. The witness refuses to become data. Because we are being turned into data. Because disappearance today does not always come by bullets, but by clicks. There is no need for concentration camps when it suffices to erase a person from official records, to render them invisible in systems, to reduce them to a line of code deleted without ceremony. For example: when a government deletes a refugee’s immigration file with a single keystroke, no body falls, but a life vanishes from the system.

And so I write. I write because I need to keep the language of testimony alive. I write because silence, in these times, may be complicity. I write like one who prays, like one who lights a candle in the dark, knowing it may not light much—but that at least, it burns.

Leave a comment