Israel Centeno

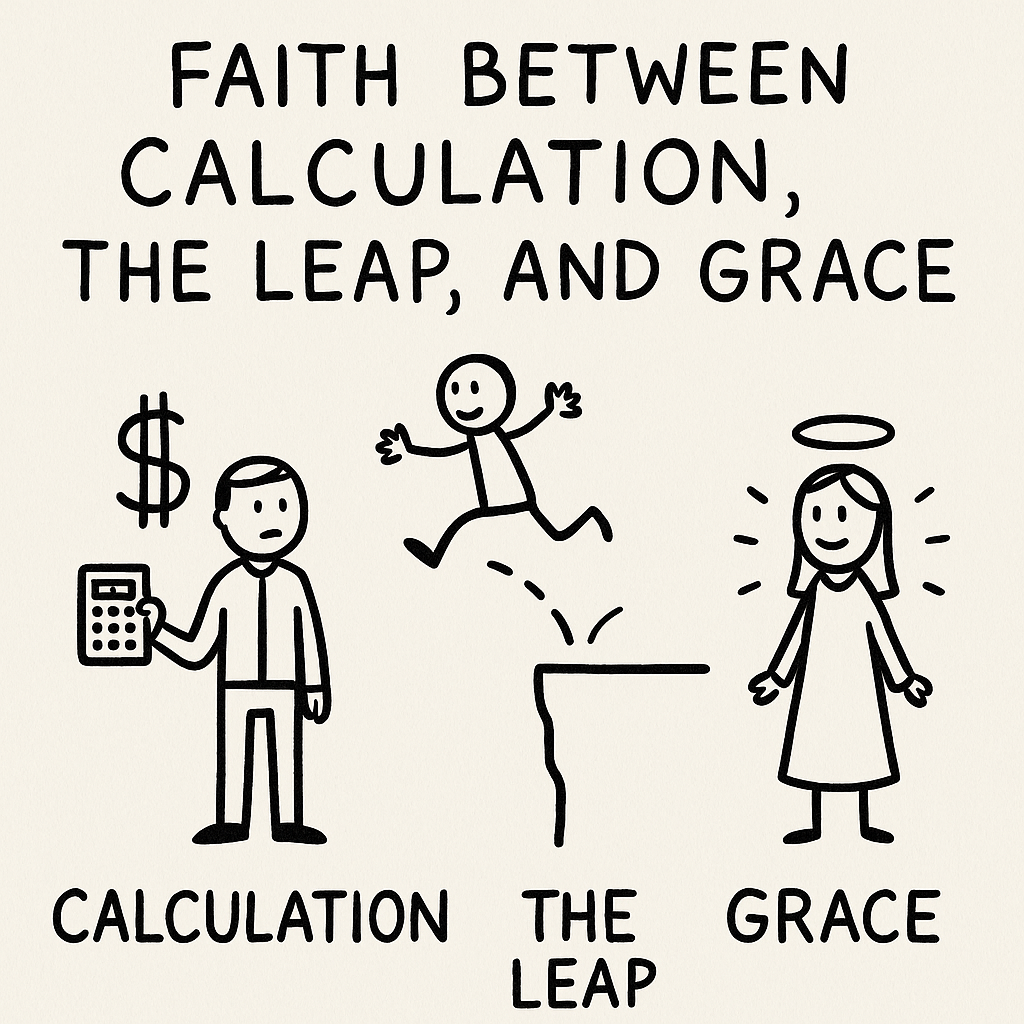

Blaise Pascal, the scientist who dialogued with God between physics experiments and nights of fire, left one of the most famous and debated proposals in philosophical history: the wager on God’s existence. He didn’t seek to prove God’s existence as a scholastic would, but to seduce modern reason through its own logic. If you believe in God and He exists, you gain everything; if He doesn’t exist, you lose little. If you don’t believe and God exists, you lose everything. From this standpoint, belief is the most reasonable choice. But this “reasonableness” is still not true faith. It is, at best, an act of prudence in facing the abyss—a metaphysical strategy to avoid complete error if God exists. It’s the prelude to a miracle—but not the miracle itself.

Pascal knew this. That’s why he didn’t stop at the logic of calculation. He added something more unsettling: “Act as though you believe, and you will end up believing.” Like tuning an instrument before understanding the music. Here starts the paradox: external acts can open the door to an internal transformation. Not because habit creates faith, but because—as Pascal suggests—God may graciously work through the repeated gesture of someone who has not yet been touched by grace.

To this cold yet passionate logic responds, from another existential galaxy, Søren Kierkegaard. To him, faith is not a wager, nor can it be feigned in hope of ignition. Faith is a leap, but not an assured leap like that of a child running into their father’s arms. It is the leap of one who leaps into the absurd. The “knight of faith,” like Abraham, walks toward sacrifice without visible promise, convinced that God will return his son, even when reality screams the opposite. For Kierkegaard, faith is scandalous, anguished, vertiginous. It is accepting that reason has reached its limit, and that only an act of absolute love can cross the abyss. The believer does not calculate benefits; he abandons himself. He does not act “as if he believes,” but ceases to live for himself to live for Someone Else.

Yet neither Pascal’s wager nor Kierkegaard’s leap suffice to explain the mystery of faith. According to St. Thomas Aquinas, faith is an act of the intellect moved by the will under the motion of divine grace. It is not produced by intellect alone, nor can the will sustain it unaided. Faith is a participation in a light that originates outside the soul, illuminating it from above. It is neither reaction to sorrow nor strategy against death, but a new way of knowing that the soul receives when God reveals Himself.

Here lies the radical distinction. Pascal invites us to consider faith as a rational option; Kierkegaard demands it as an existential necessity. Thomas, in contrast, shows that faith is a gift, uplifting reason without negating it, transforming the will without enslaving it. Faith is not leap nor wager: it is grace that beckons, touches, and summons. It is a freely made answer to an invitation only understood within the mystery of divine love.

In the end, every human being faces this crossroad at some point. One can wager, one can leap, one can wait. But if the heart does not open to grace, none of it is enough. And if grace arrives—as it always does—faith ceases to be a game of possibilities or a leap into absurdity. It becomes a silent certainty, a resting place for the soul, a fire that burns without consuming.

To believe is not to have won a bet or survived the leap. It is to be loved first

Leave a comment