Israel Centeno

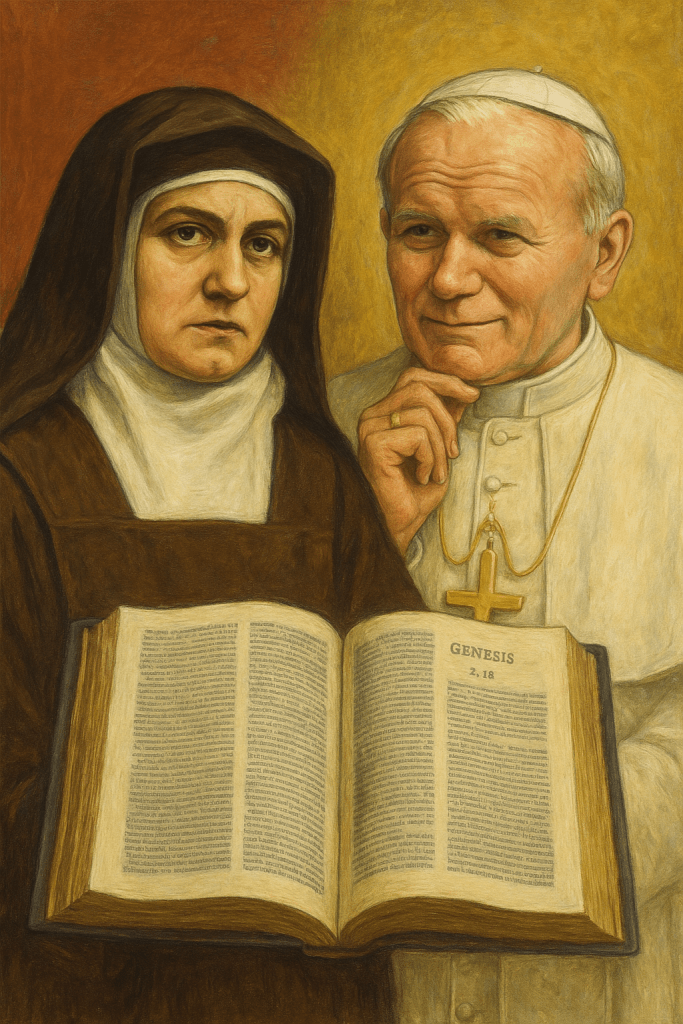

Edith Stein (St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, 1891–1942), philosopher, phenomenologist, theologian, and martyr, had a significant though indirect influence on John Paul II’s Theology of the Body (1979–1984). There are no direct quotations or textual dependencies, but rather a deep convergence of spirit and method. Both shared the intellectual project of integrating Husserlian phenomenology with Thomism—a synthesis that shaped the so-called “Lublin Thomism,” to which Karol Wojtyła belonged.

1. Intellectual Context: Thomistic Phenomenology and the Unified Person

Wojtyła encountered Stein’s writings during the 1940s and 1950s, attracted by her attempt to unite phenomenology—the rigorous study of lived experience—with the metaphysics of being in St. Thomas Aquinas. Both understood the human person as a psychosomatic unity open to transcendence. Stein, a disciple of Edmund Husserl, developed in On the Problem of Empathy (1917) and her Essays on Woman (1932) an anthropology that affirms the unity of body and soul and views empathy as the means of entering into another’s interior world. These ideas deeply resonated with Wojtyła’s own search for an integral anthropology uniting freedom, affectivity, and embodiment.

Although they never met—Stein died in Auschwitz in 1942, when Wojtyła was 22—her influence reached him indirectly through Roman Ingarden, her close friend and Wojtyła’s mentor.

2. Parallels in the Theology of the Body

Theology of the Body presents the human body as the visible sign and language of divine love. It integrates phenomenology, revelation, and Thomistic metaphysics. Stein’s indirect influence appears in three major themes:

a) Unity of Body and Soul, and Human Dignity.

Stein rejects Cartesian dualism and affirms that the body belongs to the essence of the person. Wojtyła extends this intuition by declaring the body “visible theology,” a sacrament of divine love. In the male–female difference, he sees the bodily revelation of Trinitarian communion.

b) The Vision of Woman and the Feminine.

Stein’s reflections on woman develop a “theology of the feminine” grounded in empathy and the interior disposition to love and to give. Wojtyła’s Mulieris Dignitatem (1988) expands this insight, defining “feminine genius” as the unique capacity to receive and cooperate with creative love.

c) Personalism and the Ethos of Gift.

Both thinkers affirm the irreducibility of the human person. For Stein, empathy is the path to genuine encounter; for Wojtyła, self-gift is the highest form of that encounter. In both, love is the supreme realization of personal being and the key to moral and spiritual fulfillment.

3. Reading Genesis and the Complementarity of the Sexes: Stein, Wojtyła, and the Platonic Heritage

Stein and Wojtyła share a common interpretation of Genesis: sexual difference is not hierarchy but reciprocity. “It is not good that the man should be alone” (Gen 2:18) expresses an ontological truth—human beings are created for communion. Stein interprets man and woman as complementary modes of personhood. Wojtyła formulates this insight in his concept of the “spousal meaning of the body,” in which sexual difference becomes the very language of love.

This biblical anthropology implicitly dialogues with the Platonic tradition. In Plato’s Symposium, eros is portrayed as the longing for a lost unity. Stein and Wojtyła purify that intuition through faith: love does not seek fusion but personal communion in freedom. Eros is transfigured into agape; difference becomes the sign of a higher unity, an image of Trinitarian love.

4. Personal and Ecclesial Influence of John Paul II

John Paul II explicitly recognized Stein’s spiritual and philosophical importance. He beatified her in 1987, canonized her in 1998, and proclaimed her co-patroness of Europe, calling her a “dramatic synthesis of our century.” In Fides et Ratio (1998), he cited her as a model of the philosopher who reconciles reason and faith. Her thought also inspired his “new feminism,” which echoes Stein’s vision of woman as co-worker in the economy of grace.

5. Conclusion: Spiritual Convergence and Legacy

Edith Stein’s influence on Theology of the Body is indirect yet decisive. Her phenomenological-Thomistic thought prepared the ground for Wojtyła’s theological articulation of the body as a sacrament of divine love. Both offered an anthropology of communion in which the body is not a limitation but a transparency of the spirit.

Stein did not create Theology of the Body, but she stands among its invisible roots. Her philosophy made it possible for Karol Wojtyła to express, in theological language, what she had glimpsed philosophically: that the human body is the place where the person offers, reveals, and becomes transparent to the mystery of God.

Leave a comment