Israel Centeno

If you had to picture ultimate power, what image would come to mind? Probably a warrior, invincible and untamed. A king upon a throne, majestic and feared. Or perhaps a wild animal reigning over its domain—strong, fierce, radiant. That is what humanity has always worshiped. And for good reason. In the logic of survival, strength wins. The powerful dominate. The ones who act take control.

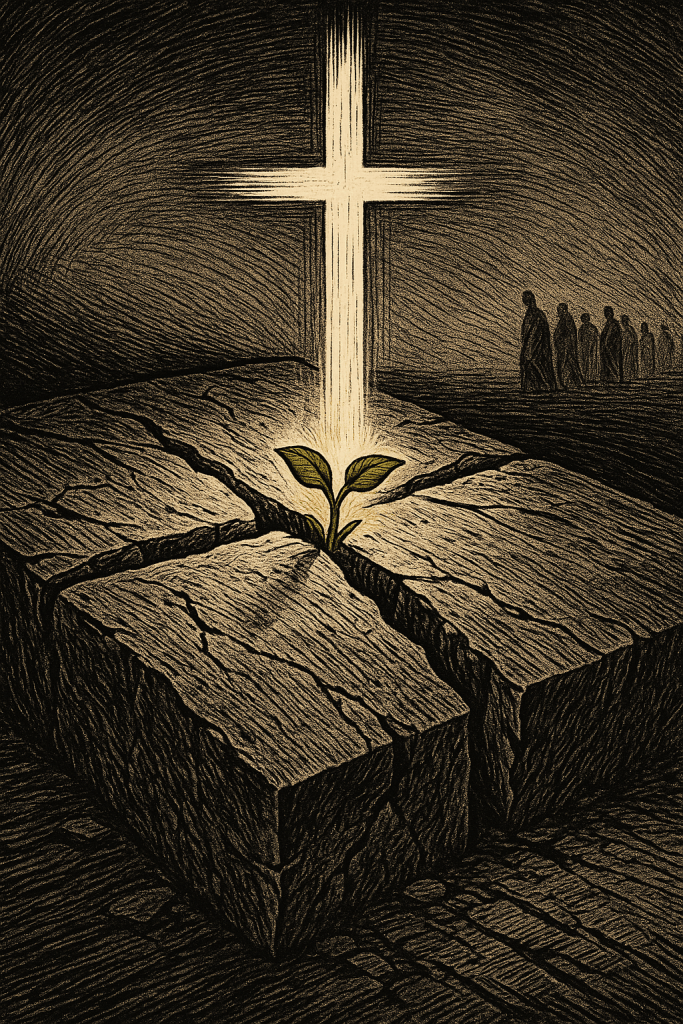

But there’s another image—one that defies all of this—not with force, but with a silence that wounds. A man nailed to a wooden cross, at the breaking point of suffering. Naked, defeated, mocked. Not a hero. Not a king. A condemned criminal. A god who dies.

And yet, over this image—this Cross—millions have built their lives, their families, their prayers, their art, their revolutions.

Not because it was beautiful.

But because, to them, it was true.

We’ve been told this is absurd. And it is. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche shouted it louder than anyone: the crucified God is the greatest offense to life. A slave morality, born of resentment, that glorifies weakness, suffering, pity, forgiveness—a revolt of the powerless against the strong. “God is dead!” Nietzsche announced. But he said it not in triumph, but in mourning. Because he knew that when that God died, something in the human soul had been broken forever.

And yet… the madness didn’t die.

It’s still alive.

And even more: it’s been embraced—as sane, as noble, as necessary. Every time someone forgives the one who betrayed them. Each time a man gives his life for a friend. Every time a mother suffers in silence so her child may live. There, in those acts that defy every rule of power and survival, the echo of the Cross resounds in the flesh of history.

It’s not efficient. It’s not rational. From an animal’s perspective, it’s suicide. Forgive your enemy? Love without limit? Find strength in weakness? Die for one who doesn’t deserve it? No pack of wolves, no orderly flight of albatrosses, no hive of bees operates this way. These are principles that, as we’ve seen, don’t support immediate survival. In the hell of history—concentration camps, war zones, betrayal—often the one who survives is the one who abandons these very ideals.

And yet… these ideas—the very ones that seem foolish to the machinery of nature—have become the pillars of what we call “a good life.” Gandhi didn’t free a nation with weapons, but with forgiveness. Martin Luther King didn’t win rights through vengeance, but through love. Mother Teresa, Óscar Romero, Viktor Frankl—all in their own ways—lived from that madness which declares: “My strength is made perfect in weakness.”

Why?

Because the human being is not just a machine. He is desire. He is memory. He is story. He is a thread—thin but unbreakable—stitching together past and present. He is not merely a stimulus-response machine. He is a “I”—a self that recognizes itself in the hesitant gaze of a six-year-old before an anthill. He does not live only in the present instant. He lives in memory. In hope. In the question: Why does any of this weigh so heavily in my soul—If, in the end, I am nothing but atoms and time?

And right there—at the very edge where science cannot go, the “hard problem” of consciousness—right there, a light cuts through. A voice from two thousand years ago that didn’t say, “I teach the truth.” Or “I point to life.” He said: “I am the truth. I am the life.”

This is not just another idea among many. Not just another philosophy. It is the center. The source. The only statement powerful enough to hold together all the questions we’ve been uncovering: Why do I remember? Why do I recognize myself? Why does pain matter? Why does forgiveness—though irrational—feel so deeply right?

Because if it’s true that there is within us an identity that endures, a consciousness that cannot be reduced to neurotransmitters, a love that is not negotiable, a dignity that remains even in slavery… then there must be a foundation in which all of this makes sense. Something that is not just an energy pulse, not a genetic error, not a fleeting pattern of information that vanishes at death.

There must be someone—or something—who says: “I am. I am the beginning. I am the return.”

And if that One exists—and reveals himself—He cannot say something small. He cannot say: “I am one teacher among many.” He must say, as One who knows: “I am the way. I am the truth. I am the life.”

Because only then—only if this Word is true—can anything else make sense at all.

Forgiveness is not madness. It is participation in a love that never runs dry.

Suffering is not meaningless. It is passage.

Weakness is not defeat. It is space for something greater.

And the Cross—the very scandal that repulsed the strong, the dying God that Nietzsche could not bear—becomes, for those who believe, the only place where love conquers death.

Maybe there are no scientific proofs.

Maybe we’ll never have a brain scan that measures the soul.

Maybe it will always be a leap.

But it’s a leap millions have taken—not out of ignorance, but out of honesty—because they’ve felt deep down that without that madness, the world would have no heart.

Because if there’s no love for the enemy, there’s no future.

If there’s no forgiveness, there’s no peace.

If there’s no self-giving, there’s no life.

And if all of that is true…

Then the voice that said: “I am the light, the truth, and the life”…

Maybe it’s not the madness.

Maybe it’s, simply—

the beginning.

Leave a comment