Israel Centeno

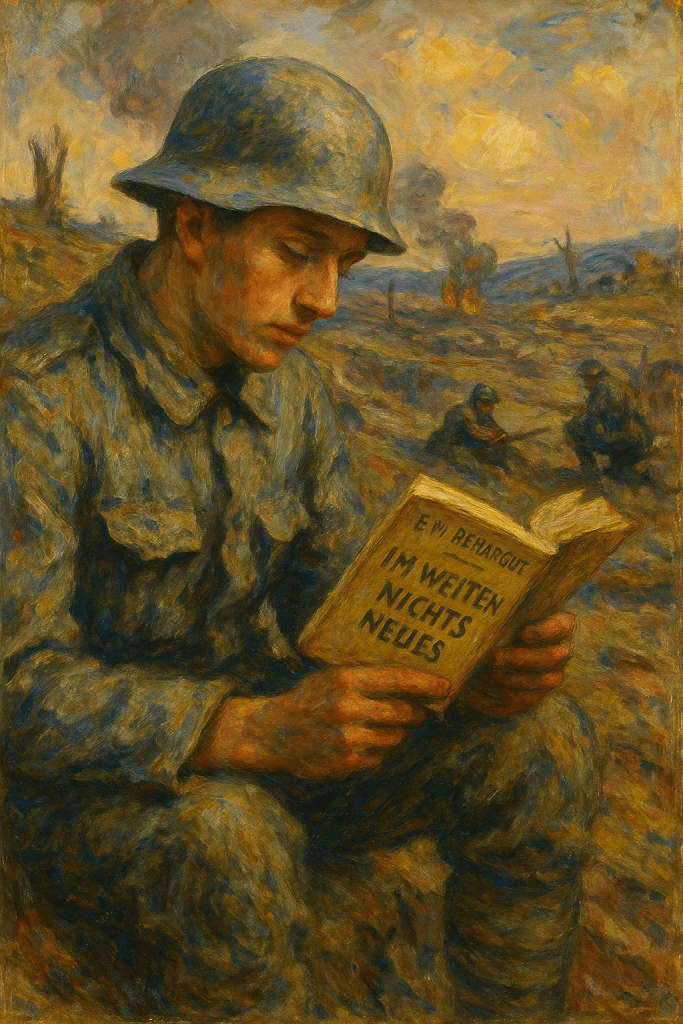

Joseph Roth’s Right and Left reads today like a warning written in the margins of European history—dense with premonitions, alive con una lucidez casi insoportable, and unsettling in its accuracy. This is not merely a portrait of the interwar years; it is an autopsy of a society drifting toward catastrophe while believing itself modern, cultured, and safe. Roth, that overlooked and silenced genius who died in Paris in 1939, had already mapped the moral genetics of what would soon become extermination, totalitarianism, and the industrialization of murder.

Far from the fashionable writers of his day—neither a nationalist prophet, nor a shallow modernist, nor a pamphleteer—Roth observes the world with a classical clarity, as if staring directly into an abyss the rest of Europe refused to name. Many readers enter his universe through The Radetzky March and stop there. But Right and Left is the real crucible: the novel in which he dissects the new bourgeoisie, the ideological hunger of lost souls, and the terrifying fusion of technology and dehumanization that would shape the twentieth century.

A Society with a Hole at Its Center

At the heart of the novel stand the Bernheim brothers—two men who embody the titular poles of “right” and “left,” not as political convictions but as interchangeable masks. One seeks refuge in nationalism; the other attempts to ascend through elegance, wealth, and social approval. Both are hollow. Both are symptoms of the same illness: a profound inner emptiness that Europe, after the fall of the Habsburg world, no longer knew how to fill.

Roth is relentless in showing that ideology—whether conservative or progressive—becomes a convenient prosthesis for the spiritually impoverished. These men do not believe in their positions; they use them as insulation. Their political identities are nothing but stage props for a civilization already slipping toward its own undoing.

Nikolai Brandeis: A Titan Who Sees Too Far

Then appears Nikolai Brandeis, one of the most enigmatic figures in Roth’s entire oeuvre: a Ukrainian peasant turned industrial magnate, a man who organizes the economic life of thousands yet walks through his own wealth as if it were smoke. He gives the new middle class its houses, its clothes, its credit, even its canaries. But what he gives most is an illusion—those “twelve hours of liberty” after work during which people believe themselves free.

Brandeis understands what no one around him sees: modern power is not human but symbolic. It rests on brass nameplates, business cards, office doors—objects more solid than the men they represent. He knows he is on the verge of becoming a servant of his own machinery, a prisoner of the very system he commands.

And it is here that Roth introduces the element that lifts this novel from social commentary to prophetic vision: chemistry.

Chemistry as the Prelude to Industrial Death

Brandeis fears only one thing—the chemical industry. The vast networks of factories, the tens of thousands of workers, the rivers of substances that can create artificial silk or poison gas, fill him with a dread no human rival could produce. In his monologue, the novel reveals something chilling: the same industrial forces that clothe society also possess the power to annihilate it.

Roth is writing before Auschwitz, yet he anticipates the moral logic that will make it possible. The danger is not chemistry itself, but a world that views technology as neutral, progress as inevitable, and human beings as malleable material. The identical industrial mentality that produces consumer comforts can, with barely a shift in intention, produce death on an unimaginable scale.

What Brandeis intuits is that Europe has already accepted this logic—long before it is weaponized.

The Genetic Code of a Coming Horror

Roth sees that the true seeds of catastrophe were already sprouting:

- casual antisemitism,

- resentful nationalism,

- political identities worn like fashionable accessories,

- a middle class craving status more than justice,

- and a growing fascination with efficiency, purity, and “improvement.”

This is the same soil in which the idea of the superhuman and the “pure race” flourished. And it is the same soil from which today’s visions of a “better,” optimized human—healthier, more effective, more efficient—emerge under new names: enhancement, optimization, transhumanism. Roth reminds us that the temptation to “improve” humanity often masks a darker willingness to discard those who fail the criteria.

Decay Is Not a Period—It Is a Human Condition

One of the novel’s deepest insights, echoed in your reflections, is that decadence does not belong to a single era. It belongs to the human creature, who moves through history broken, anxious, and desperate for meaning. The modern world, with all its ideologies and technologies, merely amplifies that fracture.

Roth’s characters live out this reality in miniature:

- Lydia, trapped in luxury yet humiliated into silence,

- Paul Bernheim, who ranks women by class and origin,

- Theodor, who clings to ideology the way a drowning man clings to driftwood.

These private degradations are the microscopic versions of the public horrors to come. Roth shows how the brutality of a century is prepared not only in parliaments or factories but in living rooms, bedrooms, theatres, and cars. The great crimes begin in the everyday.

Why Right and Left Matters Now

To read Roth today is to confront a mirror. Our world, like his, is full of hollow identities, seductive technologies, and promises of human improvement that ignore the cost. It is a world where people cling to labels—right, left, progressive, traditional—not to think, but to avoid thinking. A world where freedom often shrinks to the hours left after work. A world where economic structures operate invisibly, while human bonds erode quietly.

Roth forces us to see that none of this is accidental. The catastrophe of the twentieth century was not an aberration; it was the logical flowering of seeds long planted. And if we fail to recognize those seeds now, we risk watering them again.

His novel is not a moral lecture. It is a map—one drawn with the unflinching precision of someone que sabía demasiado. Right and Left is not just literature; it is a manual for reading the world’s fractures before they erupt.

And that is why, more than eighty years later, Roth remains indispensable. He teaches us to look without illusions, but with the kind of clarity that makes resistance—moral, social, humana—todavía posible.

La alquimia de la decadencia: Derecha e izquierda de Joseph Roth como diagnóstico de la modernidad

Derecha e izquierda se lee hoy como una advertencia escrita en los márgenes de la historia europea: densa de presagios, iluminada por una lucidez casi insoportable e inquietante en su exactitud. No es un simple retrato del período de entreguerras; es la autopsia de una sociedad que avanza hacia la catástrofe creyéndose moderna, culta y segura. Roth, ese genio subestimado y silenciado que murió en París en 1939, ya había mapeado la genética moral de lo que pronto serían el exterminio, el totalitarismo y la muerte industrializada.

Lejos de los escritores de moda de su tiempo—ni profeta nacionalista, ni modernista superficial, ni panfletario—Roth observa el mundo con una claridad clásica, como si mirara directamente al abismo que el resto de Europa se negaba a nombrar. Muchos lectores llegan a él por La marcha Radetzky y se detienen ahí. Pero Derecha e izquierda es el verdadero crisol: la novela en la que disecciona a la nueva burguesía, el hambre ideológica de las almas vacías y la inquietante fusión entre tecnología y deshumanización que definirá al siglo XX.

Una sociedad con un agujero en su centro

En el corazón de la novela están los hermanos Bernheim—dos hombres que encarnan los polos de “derecha” e “izquierda”, no como convicciones reales sino como máscaras intercambiables. Uno busca refugio en el nacionalismo; el otro intenta ascender mediante la riqueza, la elegancia y la aprobación social. Ambos están huecos. Ambos son síntomas de la misma enfermedad: un vacío interior que Europa, tras la caída del mundo austrohúngaro, ya no sabía cómo llenar.

Roth es implacable al mostrar que la ideología—ya sea conservadora o progresista—se convierte en una prótesis para quienes no tienen un centro moral. Estos hombres no creen en lo que dicen; usan sus ideas como disfraz. Sus identidades políticas son accesorios de escaparate para una civilización que ya se desliza hacia su propia ruina.

Nikolai Brandeis: un titán que ve demasiado

Entonces aparece Nikolai Brandeis, uno de los personajes más enigmáticos de toda la obra de Roth: un campesino ucraniano convertido en magnate industrial, un hombre que organiza la vida económica de miles y sin embargo atraviesa su propia riqueza como si fuera humo. Brandeis da a la nueva clase media casas, ropa, crédito, incluso canarios. Pero sobre todo les da una ilusión: esas “doce horas de libertad” después del trabajo en las que todos creen ser dueños de su vida.

Brandeis comprende lo que nadie más ve: el poder moderno no es humano, es simbólico. Depende de placas de bronce, tarjetas de visita, puertas de oficinas… objetos más reales que los hombres a los que representan. Él sabe que está a un paso de ser esclavo de su propia maquinaria, prisionero del sistema que dirige.

Y es aquí cuando Roth introduce el elemento que eleva esta novela del comentario social a la profecía: la química.

La química como preludio de la muerte industrial

Brandeis sólo teme una cosa: la industria química. Las redes gigantescas de fábricas, las decenas de miles de obreros, los ríos de sustancias capaces de producir seda artificial o gas venenoso, le provocan un terror que ningún rival humano podría inspirarle. En su monólogo, la novela revela algo escalofriante: las mismas fuerzas industriales que visten a la sociedad poseen el poder de aniquilarla.

Roth escribe antes de Auschwitz, pero anticipa la lógica moral que lo hará posible. El peligro no es la química en sí, sino un mundo que considera la tecnología como algo neutral, el progreso como inevitable y al ser humano como material manipulable. La misma mentalidad industrial que produce bienes de consumo puede, con un leve giro, producir muerte a escala masiva.

Brandeis intuye que Europa ya ha aceptado esa lógica mucho antes de que se convierta en arma.

El código genético de un horror anunciado

Roth ve que las semillas de la catástrofe ya estaban germinando:

- el antisemitismo cotidiano,

- el nacionalismo resentido,

- las identidades políticas usadas como accesorios,

- una clase media ansiosa de estatus más que de justicia,

- y la fascinación creciente por la eficiencia, la pureza y la “mejora”.

En ese terreno floreció el sueño del superhombre y de la “raza pura”. Y en ese mismo terreno brotan hoy las versiones pulidas del “humano mejorado”: más sano, más eficiente, más productivo. Roth nos advierte que la promesa de “mejorar” al ser humano suele disfrazar la disposición a descartar a quienes no cumplen los nuevos criterios.

La decadencia no es un período: es una condición humana

Una de las intuiciones más profundas de la novela—y también de tu lectura—es que la decadencia no pertenece a una época específica. Es una posibilidad constante del ser humano, que avanza por la historia roto, ansioso, buscando sentido, intentando reparar su fractura interior con ideologías, sistemas o tecnologías.

Los personajes de Roth encarnan esta verdad en lo íntimo:

- Lydia, atrapada en el lujo pero humillada hasta el silencio.

- Paul Bernheim, que clasifica el honor de las mujeres según clase y origen.

- Theodor, que abraza la ideología como salvavidas.

Estas pequeñas degradaciones privadas son versiones microscópicas de los horrores públicos que vendrán. Roth muestra que la brutalidad de un siglo se cultiva en gestos mínimos: en la manera de mirar a otro, en la forma de amar, de humillar, de callar.

Por qué Derecha e izquierda importa ahora

Leer a Roth hoy es enfrentarse a un espejo. Nuestro mundo, como el suyo, está lleno de identidades huecas, tecnologías seductoras y promesas de “mejora” humana que ignoran su costo. Es un mundo donde muchos se aferran a etiquetas—derecha, izquierda, progresista, tradicional—no para pensar, sino para evitar pensar. Un mundo donde la libertad suele quedar reducida a las horas libres después del trabajo. Un mundo donde los mecanismos económicos actúan de manera invisible mientras los vínculos humanos se desgastan.

Roth nos obliga a ver que nada de esto es casual. La catástrofe del siglo XX no fue un accidente: fue la floración lógica de semillas muy antiguas. Y si no reconocemos esas semillas hoy, corremos el riesgo de regarlas de nuevo.

Su novela no es un sermón moral. Es un mapa—trazado con la precisión sin ilusiones de alguien que veía demasiado. Derecha e izquierda no es sólo literatura: es un manual para leer las fracturas del mundo antes de que estallen.

Y por eso, más de ochenta años después, Roth sigue siendo indispensable. Nos enseña a mirar sin engaños, y esa claridad—exigente, dura, profundamente humana—es la única que aún permite resistir.

Leave a comment