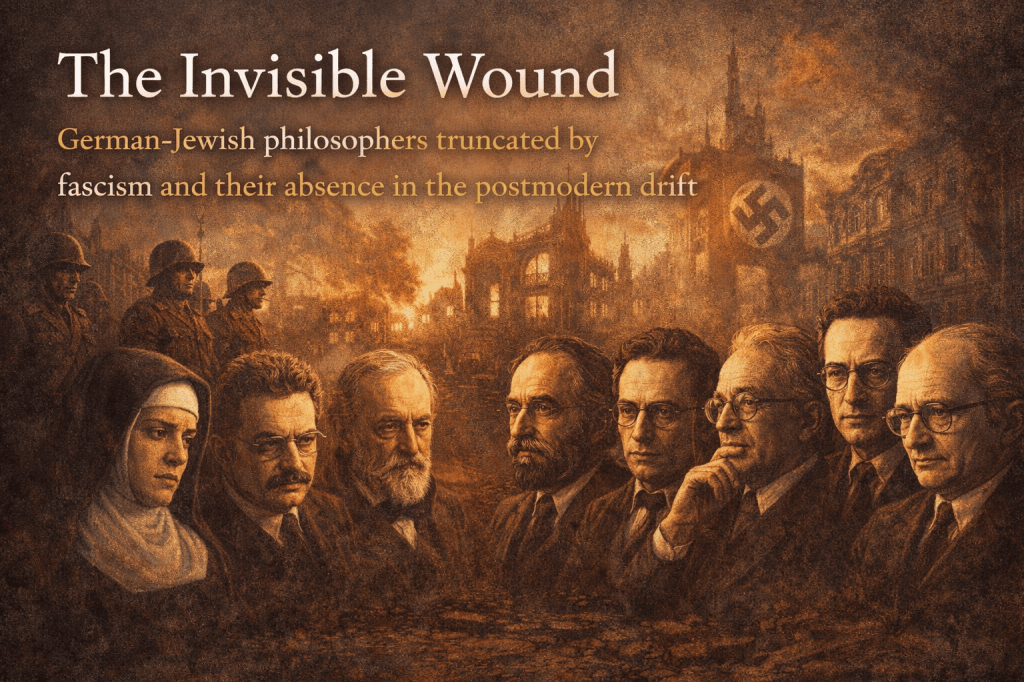

Israel Centeno

1. Philosophy as a Devastated Landscape

Some silences cannot be understood without pausing before a palpable absence. Twentieth-century European philosophy—often read through the lenses of linguistic turn, power structures, and postmodern fragmentation—did not emerge solely from internal conceptual shifts. It also arose, in large part, from a wound. A wound carved by the historical violence of European fascism, whose machinery not only annihilated lives but dismantled intellectual networks, interrupted philosophical projects, and erased entire traditions of thought whose continuation might have altered the trajectory of contemporary philosophy.

To say “postmodernity” without acknowledging this devastation is to narrate a history missing its most crucial chapter. It is like describing a ruined building without noticing the cracks in the ground on which something else was later erected. Between 1900 and 1933, Germany and its cultural circles housed an intellectual effervescence: neo-Kantianism, phenomenology, philosophy of culture, metaphysics, critical theory, and Jewish mysticism all intertwined in ways that challenged both positivist scientism and rising nihilism. What fascism destroyed was not merely a generation of thinkers—it dismantled a community of meaning.

This essay argues that the postmodern sensibility—its skepticism toward reason, its dissolution of the subject, its suspicion of grand narratives—must also be understood as the effect of an absence: the absence of a generation of German-Jewish philosophers who were developing robust alternatives to the contemporary crisis of meaning.

2. A Truncated Generation: Lives, Works, and Silences

2.1 Edith Stein: A Personalist Metaphysics Interrupted by Horror

A student of Husserl, Stein was forging an original synthesis between phenomenology and Thomistic metaphysics. Her thought sought to articulate a metaphysics of the human person—integrating experience, reason, and transcendence. For Stein, the person was not merely a semiotic node but a center of lived experience and openness to the Absolute. Her murder in Auschwitz silenced not only a life but a philosophical path that might have offered an alternative to both negative existentialism and relativistic ethics.

2.2 Walter Benjamin: The Critic of Modernity Stopped at the Border

Benjamin defied classification. Moving between Jewish theology, Marxism, and aesthetics, his unfinished Arcades Project envisioned a critical theory of modernity grounded in both material ruins and theological messianism. His suicide while fleeing fascism stands as one of the most eloquent silences of the 20th century—halting a project that could have challenged both capitalist rationality and linguistic nihilism.

2.3 Franz Rosenzweig: Redemption Interrupted

Though he died before the rise of Nazism, Rosenzweig’s reception was stifled by institutional antisemitism. His Star of Redemption developed a metaphysics of dialogue—a relation between God, world, and humanity grounded in time, history, and ethical encounter. His absence left a philosophical void: an alternative to both abstract idealism and postmodern despair.

2.4 Hermann Cohen: Repressed Ethical Humanism

Cohen, a major figure in neo-Kantian thought, argued for a rational, ethical humanism grounded in both Judaism and Enlightenment reason. The Nazis expunged his legacy from German academia. Without his influence, European moral philosophy drifted into existentialism, decisionism, or poststructuralist relativism—estranged from the ethical clarity he offered.

2.5 Ernst Cassirer: Symbolic Reason in Exile

Cassirer defended the notion that human reason expresses itself symbolically: through language, art, myth, and science. His philosophy of culture saw reason as a creative force, not a tool of suspicion. Exiled in the United States, Cassirer’s thought was largely ignored in postwar Europe, where structuralism and poststructuralism preferred critique over construction.

2.6 Hans Jonas: An Isolated Ethics for the Future

Jonas survived the Nazi era, but his thought emerged in exile, isolated from the European debates that shaped postwar philosophy. His Principle of Responsibility offered a metaphysical ethics for the future—attuned to technological power and ecological vulnerability—but was marginalized in a philosophical climate dominated by linguistic analysis and deconstruction.

2.7 Leo Strauss: Political Reason without a Home

Strauss’s recovery of classical political philosophy emphasized prudential judgment and normative reason. But in postwar Europe, his exile and the rise of critical theory left little room for such a project. His absence contributed to a void in political philosophy now occupied by anti-normative and decisionist tendencies.

2.8 Gershom Scholem: Mysticism Outside the Canon

Scholem renewed the study of Jewish mysticism, offering radical insights into language, history, and messianism. Yet his work remained on the margins of philosophical canons. The result: a European philosophy alienated from the spiritual depth and metaphysical complexity that mysticism might have reintroduced into secular thought.

3. Postmodernity as the Effect of a Void

Postwar European philosophy developed on a devastated terrain: universities dismantled, languages lost, traditions ruptured, communities of thought dispersed. In this intellectual vacuum, postmodernity gained ground—characterized by:

- the fragmentation of the subject,

- skepticism toward reason and normativity,

- the reduction of being to discourse,

- epistemological relativism,

- and the displacement of metaphysics by critique.

These features were not inevitable. They emerged, in part, because the philosophical alternatives offered by Stein, Rosenzweig, Cassirer, Jonas, Benjamin, and others were violently cut short. Their continuity would not have “prevented” postmodernity—but it might have compelled it to respond, to dialogue, to coexist with richer, deeper, and more constructive approaches to reason, subjectivity, and transcendence.

4. Conclusion: Thinking from the Wound

To speak of the “invisible wound” is not rhetorical flourish. It is to name a structural absence that shapes the very conditions of thought today. Contemporary philosophy in Europe did not merely inherit a crisis of modernity—it inherited the aftermath of destruction, the silence of what could have been.

To recover these thinkers is not nostalgia. It is a philosophical act of reconstruction. They do not simply belong to the past; they are nodes of unrealized futures. They offer not a return, but a reopening—of metaphysics, ethics, and political reason—grounded in the possibility that thinking can still begin from the wound, and not end in it.

Leave a comment