Israel Centeno

Mimetic Violence, Political Sacrifice, and Memory in the Algorithmic Age

Every political killing has two stages: the one where someone dies, and the one where society decides what that death means.

The assassination of Charlie Kirk, on September 10, 2025, at Utah Valley University, belongs fully to the second stage — the struggle over meaning.

It is not enough to know who pulled the trigger; the real question is why the nation needed to speak about it.

This essay approaches that question through the lens of René Girard, the thinker who saw in human history a chain of imitated desires, mirrored hatreds, and sacrificial victims chosen to restore order.

The point is not to judge the murderer, nor to canonize the victim.

It is to understand how a polarized society turns a crime into a myth.

Desire, Reflected

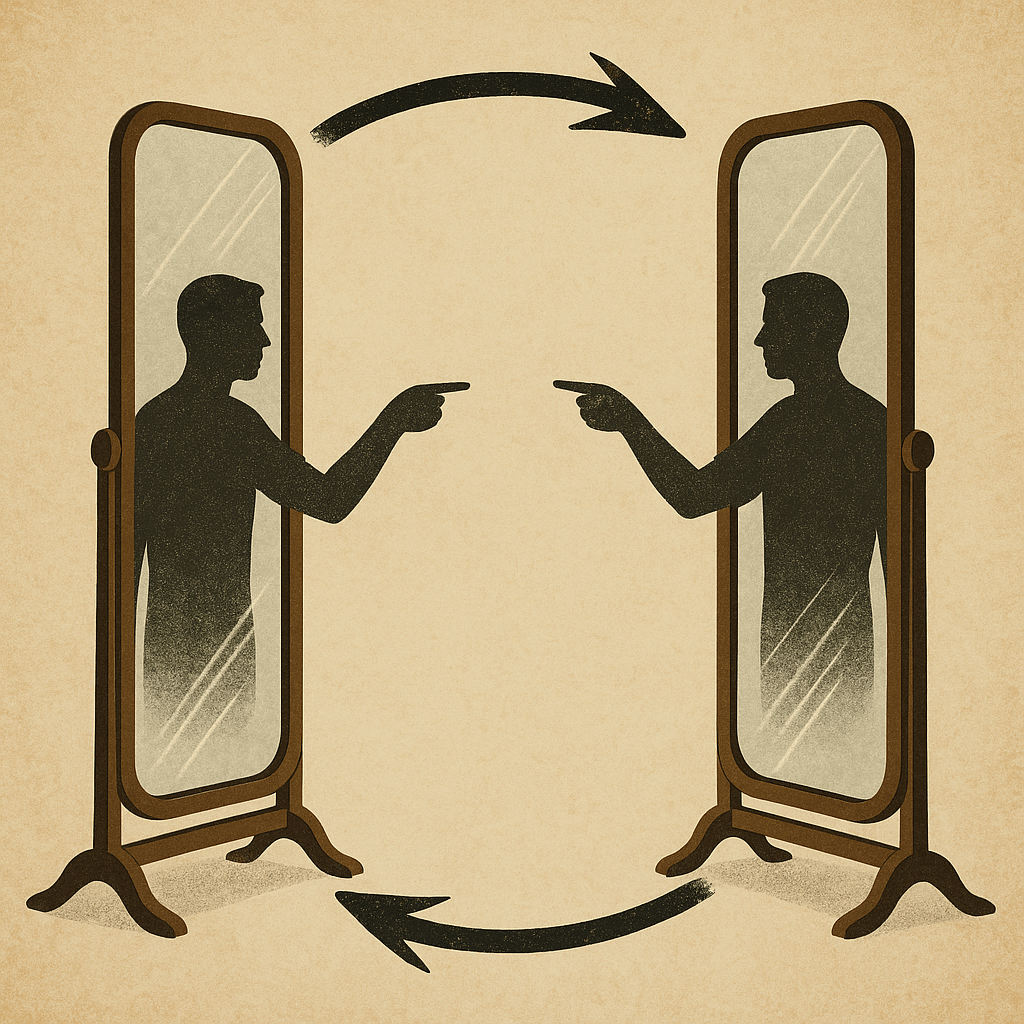

Girard wrote that human beings don’t desire things — they desire what others desire.

The enemy isn’t the opposite; he’s the mirror.

And when two groups face one another with absolute conviction, they begin to copy each other’s methods, their anger, even their purity.

Modern America is trapped in that reflection.

Two political tribes, both claiming moral high ground, mirror each other’s indignation.

Every word, every misstep, every provocation is amplified by social media until it becomes ritual.

The murder of Charlie Kirk followed the same pattern: within minutes, it was a symbol — a martyrdom for some, a cautionary tale for others.

Each side used the event to confirm what it already believed.

Girard would have recognized in this a perfect example of mimetic rivalry: the cycle in which violence reproduces itself by imitation, each enemy shaped by the image of the other.

The Sacrifice and the Myth

Every society in crisis looks for a figure to bear its guilt.

That person — the scapegoat — gathers all the tension, the anger, the unresolved fear.

Their elimination, physical or symbolic, promises release.

Girard called this the sacrificial mechanism, the ancient way of turning chaos into order.

The victim’s death, he said, founds meaning.

They become, paradoxically, both guilty and sacred — condemned and necessary.

Civilizations are built on that paradox.

In the days that followed Kirk’s death, his name entered that ambiguous space.

There were vigils, denouncements, theories, elegies, and outrage.

For some, he was a prophet struck down; for others, the embodiment of an ideology whose own fire consumed him.

Either way, his death organized the chaos, if only for a moment.

It gave everyone a story to tell.

The Algorithm as the New Altar

Once, the altar stood at the center of the city — the place where sacrifice brought peace.

Now that altar is the digital feed.

It is there that our new rituals of division and unity are performed.

Blood no longer stains the stone; it circulates in headlines, hashtags, and the endless cycle of outrage.

The algorithm has become our high priest.

It chooses what we see, whom we hate, and how often we repeat the story.

Not out of malice, but design: division keeps us scrolling.

Outrage is profitable.

In this way, mimetic violence has been automated.

Artificial intelligence, without intent or malice, extends the same sacrificial logic Girard described half a century ago — but at machine speed.

Conspiracy: The Craving for a Total Story

After an assassination comes the need to explain it.

And because no explanation is ever enough, the mind turns to conspiracy.

The killer becomes a puppet; unseen powers are blamed; the narrative expands until it feels total.

Conspiracy comforts because it gives shape to the void.

Girard would have recognized this impulse as another form of sacrifice — an attempt to locate evil in a single agent, to purify the world by naming a culprit.

Both scapegoating and conspiracy arise from the same desire: to contain chaos, to make pain intelligible.

The Peace That Isn’t Peace

After the sacrifice, there is calm.

The community feels united.

Speeches are made, candles are lit, and for a while the divisions seem suspended.

But that peace is a lie — it lasts only until a new enemy is chosen.

In Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, Girard saw in the Gospels a revelation that shattered this pattern.

Christ’s innocence exposes the mechanism itself: the scapegoat is not guilty, and violence cannot save.

True peace cannot be built on the death of another.

Modern politics, having forgotten that revelation, returns to the same ritual — only now, the sacrifices are televised, digitized, and monetized.

The altar glows in pixels.

What Girard Explains — and What He Doesn’t

Girard does not solve a crime; he reveals the grammar of collective emotion.

He doesn’t tell us who pulled the trigger, but how we react when someone dies in the name of something.

He shows us the structure of hatred, not its biography.

Through that lens, the assassination of Charlie Kirk becomes more than a tragedy — it becomes a mirror.

A society sees in it what it already fears: itself.

But Girard’s theory cannot replace justice or the facts of the investigation.

It is not an alibi; it is a diagnosis.

Breaking the Cycle

If sacrifice brings only a false peace, then the only real solution is to refuse its logic.

To stop using death as argument.

To mourn without weaponizing grief.

Some practical ethics follow from that insight:

- Double De-Sacralization. Neither demonize your adversary nor canonize your own dead. Compassion must have no faction.

- Rigor in Verifying Information. Not everything that circulates is true. Delay your conclusions. Check sources. Distinguish between fact and conjecture. Speed is not wisdom.

- Civic Rituals of Mourning. Honor life without turning death into political capital.

- Non-Mimetic Leadership. Seek leaders who refuse reflexive outrage, who choose restraint over spectacle.

- The Pedagogy of Disagreement. Learn to argue without dehumanizing. A good disagreement is the first antidote to violence.

Epilogue: Memory and Shadow

The death of Charlie Kirk is more than a tragic episode; it is a mirror held up to the age.

In it, we can see our oldest instincts and our newest technologies intertwined.

Girard might say that we are still trying to found peace on a victim — only now the sacrifice is streamed live.

Yet another possibility remains.

To recognize the victim, not to use them, but to stop the cycle.

To name the act as a crime, the grief as grief, without turning blood into a slogan.

Only then — when we relinquish the pleasure of blame — can true reconciliation begin.

A peace without sacrifice.

A memory without myth.

A future that does not need more victims.

🇪🇸 René Girard y el asesinato de Charlie Kirk

Violencia mimética, sacrificio político y memoria en la era algorítmica

Todo crimen político tiene dos escenarios: el real, donde alguien muere; y el simbólico, donde la sociedad decide qué significa esa muerte.

El asesinato de Charlie Kirk, el 10 de septiembre de 2025 en la Utah Valley University, pertenece plenamente a este segundo escenario: el de la disputa por el sentido.

No basta con saber quién disparó; la pregunta real es por qué el país necesitó hablar de ello.

Este ensayo aborda esa pregunta desde la mirada de René Girard, el pensador que vio en la historia humana una cadena de deseos imitativos, odios reflejados y víctimas sacrificiales elegidas para restaurar el orden.

No se trata de juzgar al asesino ni de canonizar a la víctima.

Se trata de entender cómo una sociedad polarizada convierte un crimen en mito.

El deseo reflejado

Girard escribió que los seres humanos no desean cosas, sino lo que otros desean.

El enemigo no es el contrario: es el espejo.

Y cuando dos grupos se enfrentan con convicción absoluta, terminan copiándose: en métodos, en lenguaje, en furia y pureza.

La América contemporánea está atrapada en ese reflejo.

Dos tribus políticas, ambas convencidas de su superioridad moral, se reflejan en su propia indignación.

Cada palabra, cada error, cada provocación se amplifica hasta volverse ritual.

El asesinato de Charlie Kirk siguió ese patrón: en minutos ya era símbolo — martirio para unos, advertencia para otros.

Cada bando usó el hecho para confirmar lo que ya creía.

Girard habría reconocido ahí el ciclo perfecto de la rivalidad mimética: una violencia que se reproduce por imitación, cada enemigo moldeado por la imagen del otro.

El sacrificio y el mito

Toda sociedad en crisis busca una figura que cargue con su culpa.

Esa figura —el chivo expiatorio— reúne la tensión, la ira, el miedo sin nombre.

Su eliminación, real o simbólica, promete alivio.

Girard llamó a eso el mecanismo sacrificial, la antigua manera de transformar el caos en orden.

La muerte de la víctima, decía, funda sentido.

Se vuelve, paradójicamente, culpable y sagrada, condenada y necesaria.

Las civilizaciones se erigen sobre esa contradicción.

En los días que siguieron a la muerte de Kirk, su nombre habitó ese espacio ambiguo.

Hubo vigilias, teorías, elegías, furias.

Para algunos fue un profeta caído; para otros, el producto de una ideología devorada por su propio fuego.

En ambos casos, su muerte organizó el caos, aunque fuera por un instante.

Dio a todos una historia que contar.

El algoritmo como nuevo altar

Antes, el altar estaba en el centro de la ciudad: allí donde el sacrificio traía la paz.

Hoy ese altar es el feed digital.

Ahí se celebran nuestros nuevos rituales de división y unidad.

La sangre ya no mancha la piedra: circula en titulares, hashtags y el interminable ciclo de indignación.

El algoritmo es el nuevo sumo sacerdote.

Decide lo que vemos, a quién odiamos y cuántas veces repetimos la historia.

No por malicia, sino por diseño: la división mantiene la atención; la atención genera beneficio.

Así, la violencia mimética se ha automatizado.

La inteligencia artificial prolonga, sin saberlo, la lógica sacrificial que Girard describió hace medio siglo, pero ahora a velocidad de máquina.

La conspiración: hambre de una historia total

Después de un asesinato llega la necesidad de explicarlo.

Y como ninguna explicación basta, surge la conspiración.

El asesino se vuelve instrumento; el mal tiene un rostro oculto; la narrativa se expande hasta parecer completa.

La conspiración consuela porque le da forma al vacío.

Girard habría reconocido ahí el mismo impulso: localizar el mal en un solo agente, purificar el mundo nombrando a un culpable.

El chivo expiatorio y la conspiración nacen del mismo deseo: contener el caos, volver el dolor comprensible.

La paz que no es paz

Tras el sacrificio, llega la calma.

La comunidad se siente unida.

Se pronuncian discursos, se encienden velas, y por un momento las divisiones parecen suspenderse.

Pero esa paz es falsa: dura hasta que aparezca un nuevo enemigo.

En Las cosas ocultas desde la fundación del mundo, Girard vio en el Evangelio una revelación que rompe el ciclo: la víctima es inocente, y la violencia no redime.

La paz verdadera no puede construirse sobre la muerte del otro.

La política moderna, olvidando esa revelación, repite el mismo ritual: los sacrificios siguen, solo que ahora son televisados, digitalizados y monetizados.

El altar brilla en píxeles.

Lo que Girard explica —y lo que no

Girard no resuelve crímenes: revela la gramática de la emoción colectiva.

No dice quién disparó, sino cómo reaccionamos cuando alguien muere “por algo”.

Nos muestra la estructura del odio, no su biografía.

Desde esa mirada, el asesinato de Charlie Kirk es más que una tragedia: es un espejo.

Una sociedad se ve a sí misma en aquello que teme.

Pero la teoría girardiana no sustituye la justicia ni los hechos.

No es un pretexto: es un diagnóstico.

Romper el ciclo

Si el sacrificio ofrece solo una paz falsa, la única salida es rechazar su lógica.

Dejar de usar la muerte como argumento.

Llorar sin convertir el duelo en arma.

Algunas éticas prácticas pueden servir:

- Doble des-sacralización. No demonizar al enemigo ni canonizar al propio muerto. La compasión no tiene partido.

- Rigor en la verificación informativa. No todo lo que circula es cierto. Esperar, contrastar, distinguir entre hecho y conjetura. La rapidez no es sabiduría.

- Rituales cívicos de duelo. Honrar la vida sin convertir la muerte en capital político.

- Liderazgo no mimético. Buscar voces que rehúyan la furia reflejada y el espectáculo.

- Pedagogía del desacuerdo. Aprender a discutir sin deshumanizar. Un buen desacuerdo es el primer antídoto contra la violencia.

Epílogo: memoria y sombra

El asesinato de Charlie Kirk no es solo un episodio trágico: es un espejo del tiempo.

En él se cruzan nuestros instintos más antiguos y nuestras tecnologías más nuevas.

Girard diría que seguimos intentando fundar la paz sobre la víctima, solo que ahora el sacrificio se transmite en vivo.

Pero aún hay otra posibilidad.

Reconocer a la víctima, no para usarla, sino para detener el ciclo.

Nombrar el crimen como crimen, el duelo como duelo, sin convertir la sangre en consigna.

Solo entonces —cuando renunciamos al placer de culpar— puede empezar la verdadera reconciliación.

Una paz sin sacrificios.

Una memoria sin mito.

Un futuro que no necesite más víctimas.

Leave a comment