Time, Memory, and the Paradox of Theseus’ Ship

Israel Centeno

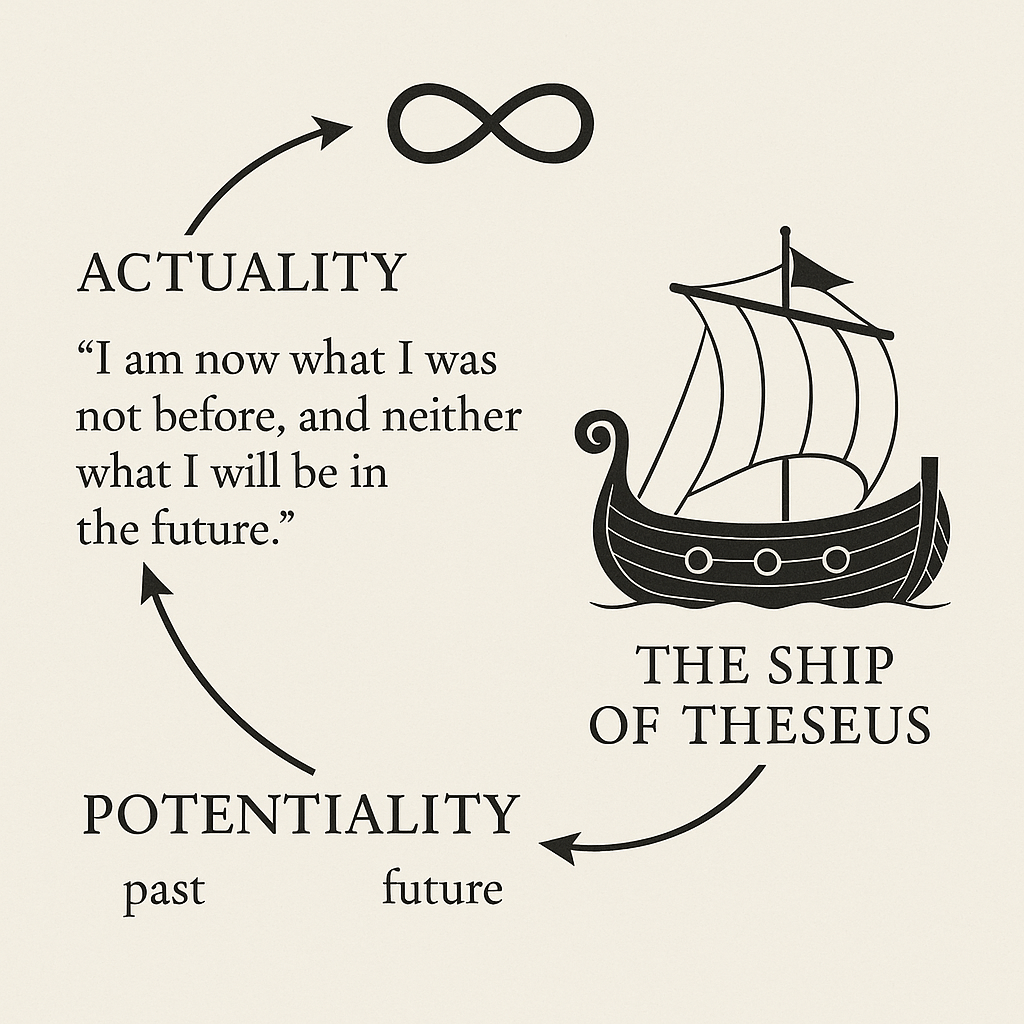

“I am now what I was not before, and neither what I will be in the future.”

Who am I, if everything in me changes? What remains, if the experience of the present transforms me, memory reconfigures me, and death strips me of the body? These questions confront us with the most intimate mystery of existence: the permanence of being amid becoming.

I. Theseus’ Ship and Identity in Change

The classic paradox of Theseus’ ship asks whether an object that has had all its components replaced remains the same object. Applied to the human being, the question becomes even deeper: if my cells change, if my memories shift, if my emotions and desires transform, am I still the same?

This paradox does not merely present a logical puzzle—it reveals a foundational intuition: identity is not an immobile substance but a structured continuity, a form that persists while its matter flows. In Aristotelian terms, being manifests as act and potency: I am actual in my present, but I contain the potency of what I was and of what I will be.

II. Time as the Horizon of Finite Being

Time is not a neutral container in which change happens. For the conscious being, time is a lived dimension. Augustine of Hippo put it clearly: the past is memory, the future is expectation, the present is attention. Time, then, is not merely what passes but what the soul preserves.

Without memory there is no time, only disconnected instants. The finite being constructs its identity by narrating itself, by engraving within a flow that becomes history. This is why death doesn’t only raise the question of the body, but of that interior imprint: where does my identity go? Is it dissolved or preserved?

III. Memory as the Inscription of Being

Memory is not only recollection but configuration of the self. Through it, the finite being reorders its experiences and recognizes itself. We are memory constantly updating, reworking the past and projecting the future. The being records, and in that recording, it sustains itself.

And even if the body dies, might not that memory—that recorded mode of being—be susceptible to another form of existence? Here opens the possibility of a transcendence that does not negate time but elevates it: an eternalized memory, not as repetition but as fulfillment.

IV. Actuality, Potentiality, and Life After Death

From Thomistic metaphysics, every being actualizes what was once in potency. Human life is constant actualization: we are born with potentialities that, as they develop, configure us as subjects. But if there is in us a spiritual principle—not reducible to matter—then that actualization can continue beyond death.

Christianity proposes that identity is not lost but transfigured in the resurrection, not as exact material restoration but as the permanence of the self in its totality. The glorified body is the final form of that personal continuity.

V. Conclusion: Between the Passing Now and the Enduring Self

The human being lives a paradox: always changing, yet recognizing itself as the same. It is act, but also potency. It lives in time, but desires eternity. Its “I” is made of present, but woven from past and projected toward the future.

Just as Theseus’ ship remains the same while it changes, I am “I” as I transform, because something—a form, a memory, a vocation for meaning—remains.

And if that “something” has a divine origin, then its destiny cannot be annihilation, but fullness.

Leave a reply to landzek Cancel reply